America may not have had a coherent foreign policy since the end of World War II. And the beat goes on.

Incoherence doesn’t mean that there haven’t been successes. It doesn’t mean that other countries have done better in that time. And it doesn’t mean that the era has been an easy one: the world is more complex and diffracted than ever.

Coherence means an open, intelligent discussion about principles, followed by an open, intelligent discussion about taking action or withholding, and about the consequences and aims of the paths we choose or avoid.

Our policy seems to be driven by overwhelming ideology, good intentions and self-interest—none of which are exceptional or indictable, but all of which should be expressed in a much bigger and more sensible and realistic context. We ought to know what we’re about and candidly tell our citizens what we’re about. And when we don’t know what we’re doing—hard as that is to admit—we ought to say so.

Harry Truman was the last President to have a foreign policy named after him, in that case the Truman Doctrine. In 1947 he warned that the U.S. and the free world could not stand for Greece and Turkey falling into Communist hands (though he never used the word Communism):

It is necessary only to glance at a map to realize that the survival and integrity of the Greek nation are of grave importance in a much wider situation. If Greece should fall under the control of an armed minority, the effect upon its neighbor, Turkey, would be immediate and serious. Confusion and disorder might well spread throughout the entire Middle East….

It would be an unspeakable tragedy if these countries, which have struggled so long against overwhelming odds, should lose that victory for which they sacrificed so much. Collapse of free institutions and loss of independence would be disastrous not only for them but for the world. Discouragement and possibly failure would quickly be the lot of neighboring peoples striving to maintain their freedom and independence.

Should we fail to aid Greece and Turkey in this fateful hour, the effect will be far reaching to the West as well as to the East.

March 12, 1947

(A digression: The reason Greece was considered vulnerable to insidious forces in 1947 is that it was broke and falling apart. Presumably, without a Communist threat looming, Greece 2013 is no longer considered as significant.)

That black-and-white view was in some ways a vestige of the black-and-white war we had just finished—and won. But soon after that speech, global gray was the new black-and-white. Empires were crumbling, new nations were being made. In the year of the Truman Doctrine alone, two of the world’s most populous nations changed course: India became independent, Mao won a revolution in China—events representing more than a third of the world population. The following year, the Middle East (and history) came unglued forever with the creation of Israel. We could pretend that all this was part of some simple monolithic history, but that really made no sense.

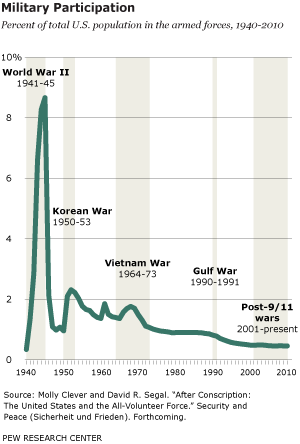

And yet we proceeded with a dyadic us-versus-them model for decades, mostly inexplicably and unquestioningly. Korea was supposed to stop the Communism; the military result was a bloody stalemate and status quo, the economic result a Chinese hegemon. Vietnam was supposed to stop Communism; we lost the war, and Southeast Asia is a geopolitical hodgepodge. Soviet Communism crumbled, partly because of a changing world and culture, partly because being a Russian non-Communist economic and political oligarch is much more lucrative than being a party apparatchik.

When we were attacked by the Muslim Middle East, our policy was to strike back, just as we had after Pearl Harbor. Never mind that the policy was sixty years old, and that the complexities of the world could not possibly be much affected by those approaches. Sadaam Hussein is dead, and Iraq is descending at some speed into chaos. Afghanistan is or soon will be about where we found it. Osama Bin Laden is dead, but just as with the Taliban, even if Al Qaeda is diminishing, movements with other names are already rising up to take its place.

All that is preface to our incoherence in Syria.

It is easy to see why the chemical weapon “red line” matters and why proving that it has been crossed matters.

The brutality of World War I made us rethink just far we would go and where as a ‘civilized” world we would draw the line. The Geneva Protocol of 1925 prohibits their use. The community of nations has, more or less, stood behind this and its successors.

(Another digression: If the world had considered the real possibility of atomic weapons in this period between the wars, would these also have been put in the same prohibited category as chemical and biological weaons?)

The reason for taking such care about making sure the line is actually crossed of course goes back to Iraq. Having cried wolf so recently, the U.S. could not stand having its credibility questioned, internally or externally, on the issue of weapons of mass destruction.

But as the drumbeat for “doing something” gets louder in the wake of the U.S. now being completely confident that chemical weapons were used by the Assad regime, so many questions are not being asked, and if asked, not discussed or answered.

If we are already confident that thousands are killed, tens of thousands injured, hundreds of thousands displaced, and a nation is being destroyed from inside, why was the imperative waiting for this line at all? There is a global political answer, of course, which is that chemical weapons are a bigger and less assailable common ground upon which most or all can agree. That is indeed a pragmatic strategy, but we also have to talk about moral imperatives, no matter which way the discussion goes.

What exactly can and should we do? And if we do act, what do we expect and hope will be the result? And if we do act, what are the potential consequences?

Our leaders can talk about the red line in Syria, but they should stop pretending that this amounts to coherent and deep consideration. The three questions of actions, expectations and consequences should be the topic that consumes us. If we have principles and doctrines, let’s put them on the table and inspect them and see how aspirational and practical they are. If we believe in sovereignty in some cases but not others, let’s make sure that we know what the cases are and why the distinctions matter. If we do or don’t intervene in foreign political matters or insurrections or civil wars, let’s talk about it and how we act or react.

Instead, what we get are red lines and, in the case of Egypt, the sight of the U.S. being unwilling to call a coup a coup, and otherwise being paralyzed in figuring out what to do or say, so that “subtle” back channel goings on can go on.

Subtle goings on or silence can also may mean that you don’t know what to do or say, or that you don’t want the greater citizenry to hear what you are actually thinking. Maybe our leaders really aren’t very good at being statesmen. Maybe that citizenry isn’t up to the task of having discussions about what we believe, what we can accomplish and what we can’t. The only way to know this is to have it out in the open.

We seem to be more comfortable in the black and white and red line world of the Truman Doctrine. That wasn’t even a true picture of the world seventy years ago, and it definitely isn’t today. Can we talk, without slogans, without the fairy tale that the world of 2013 is a place that will resolve to our political and moral satisfaction soon—or ever? Before we make one more mistake, we have to find out.

Tin is the traditional gift to mark a 10th wedding anniversary, just as it is silver for the 25th and gold for the 50th. There is no tradition about the anniversaries of wars, so tin will have to do.

Tin is the traditional gift to mark a 10th wedding anniversary, just as it is silver for the 25th and gold for the 50th. There is no tradition about the anniversaries of wars, so tin will have to do.