Today the Supreme Court hears arguments in the case of ABC, et al. v. Aereo. Some characterize it as the most important media case in decades, one which could destroy broadcasting as we know it.

That is both overstated and understated. The big broadcasters who claim this is the apocalypse won’t go out of business; they will continue, though they might make a little less money or have to work a little harder for it. On the other hand, nothing less than the nature of modern reality is being considered, which is what makes the case so interesting and ultimately so hard to decide.

In a nutshell, this is what Aereo does:

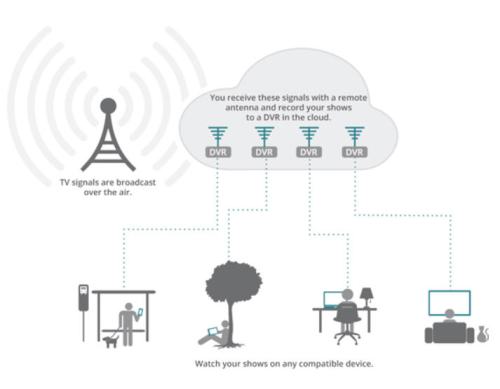

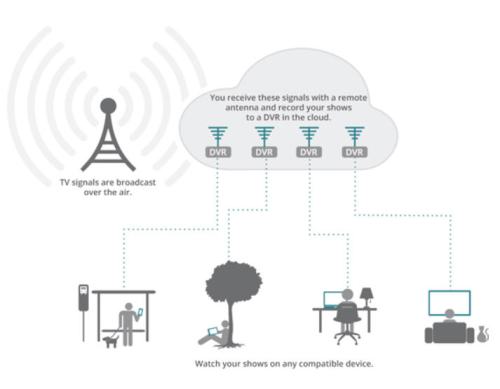

Aereo sets up lots of tiny (thumbnail) antennas in your locality.

The antennas pick up the same over-the-air (OTR) TV signals you would if you had an antenna at your home (but you probably don’t).

You subscribe to Aereo for as little as $8 a month.

When you want to watch something from the stations that are on the air in your locality, Aereo assigns you an antenna, collects and records the signal from that antenna in its cloud, and streams that signal the way you want to the device you want, now or later.

The question is whether Aereo is retransmitting copyrighted content to subscribers, cleverly skirting retransmission fees that cable systems and others must pay, which would be stealing. Or whether Aereo is simply enabling you to do something you are legally entitled to do: receive OTR TV and then watch it, record it, or redistribute it to your own devices for your own personal use.

The Second Circuit Court of Appeal decided in favor of Aereo, with a vigorous dissent and with other Circuit Courts disagreeing, and now the Supreme Court will decide. If you read the briefs you can get an idea of the difficulty and the possible impacts.

One can say, as the big broadcasters do, that Aereo may be trying to fit through a loophole in the law, but that isn’t quite right. Aereo is taking advantage of a reality so profoundly new and so newly understood that every medium and every media business is just barely beginning to come to grips.

When you reduce things to information and can move that information around infinitely and frictionlessly and at relatively low cost, the processes and regulations meant to handle grosser things are of limited value.

First a book was a thing made of paper, then there was a copier which could copy pages on paper, then there was a scanner that could turn paper pages into digital images and, with OCR, characters, then there were entire books that never had anything to do with paper, ever, just pure arranged information. The same goes, with slightly different details, for every medium. The solution for the producers who wanted to control things (often with legitimate interests, such as creators being compensated), was to put the information in some kind of box, which to some looked like an information jail. It was and is this simple: once it gets out of the box, catching it and catching up with it is quite a chore. Because, as Stewart Brand famously said, information wants to be free.

If you had to characterize the actors in this case as good guys or bad guys, it does look like ossified old school versus new school, mega-corporations versus insurgents, or as one of the briefs says, David versus Goliath. Any way you put it though, and wherever your opinion lies, this is a hard case, and the maxim is that hard cases make bad law. In this case, bad law would mean that even if progressive principles are maintained, more looking forward than back, we are still in an astonishing mess when it comes to dealing with all this. One case at a time won’t do, and the expectation that Congress will seize the reins and lead us boldly into an enlightened future on digital intellectual property is, at least for the moment, not in the cards or the cloud.