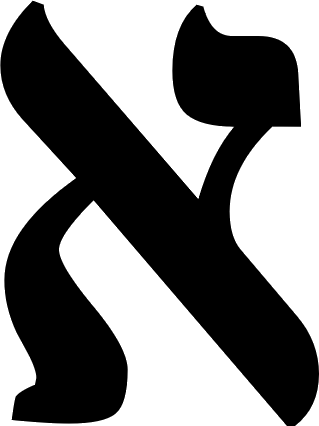

Meditation: Why does the Hebrew Bible begin with the letter Bet (Bereshit—In the beginning) and not the first letter Aleph?

The Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) begins with the Hebrew word “Bereshit”, conventionally translated as “In the beginning”.

In Hebrew the word begins with the second letter of the alphabet, Bet, like the second letter B.

But it is the beginning. So why doesn’t the text start with an Aleph/A word, the first letter of the alphabet?

This is a conundrum that has challenged the rabbis for centuries. They have spoken and written insightfully at length about it.

You don’t have to know what the rabbis have said or written. You don’t have to be Jewish, you don’t have to know Hebrew. You don’t have to be a student of the Bible. You already know enough, as detailed above.

Instead, consider this like a Zen koan, something to ponder without resolving. If it helps your pondering, whether you know Hebrew or not, you might look at and contemplate the image of the letters. Is there something about the letters themselves that tells you something about why one was chosen instead of the other to start off this famous story?