Whether or not you believe in religion, God, Judaism or the Torah, it is exciting that the annual cycle of Torah reading begins again with the first words of Genesis. A Big Nothing? A Big Something that becomes a different Big Something? Who knows? Who even knows what it says?

Here, a few different translations and comments from some brilliant scholars.

GENESIS 1:1-2

בְּרֵאשִׁ֖ית בָּרָ֣א אֱלֹהִ֑ים אֵ֥ת הַשָּׁמַ֖יִם וְאֵ֥ת הָאָֽרֶץ׃

הַמָּֽיִם׃ וְהָאָ֗רֶץ הָיְתָ֥ה תֹ֙הוּ֙ וָבֹ֔הוּ וְחֹ֖שֶׁךְ עַל־פְּנֵ֣י תְה֑וֹם וְר֣וּחַ אֱלֹהִ֔ים מְרַחֶ֖פֶת עַל־פְּנֵ֥י

When God began to create heaven and earth, and the earth then was welter and waste and darkness over the deep and God’s breath hovering over the waters

Note:

welter and waste. The Hebrew tohu wabohu occurs only here and in two later biblical texts that are clearly alluding to this one. The second word of the pair looks like a nonce term coined to rhyme with the first and to reinforce it, an effect I have tried to approximate in English by alliteration. Tohu by itself means “emptiness” or “futility,” and in some contexts is associated with the trackless vacancy of the desert.

hovering. The verb attached to God’s breath-wind-spirit (ruaḥ) elsewhere describes an eagle fluttering over its young and so might have a connotation of parturition or nurture as well as rapid back-and-forth movement.

Robert Alter, The Hebrew Bible: Translation with Commentary

When God began to create heaven and earth—the earth being unformed and void, with darkness over the surface of the deep and a wind from God sweeping over the water—

Note:

A tradition over two millennia old sees 1.1 as a complete sentence: “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.” In the 11th century, the great Jewish commentator Rashi made a case that the verse functions as a temporal clause. This is, in fact, how some ancient Near Eastern creation stories begin—including the one that starts at 2.4b. Hence the translation, When God began to create heaven and earth.

This clause describes things just before the process of creation began. To modern people, the opposite of the created order is “nothing,” that is, a vacuum. To the ancients, the opposite of the created order was something much worse than “nothing.” It was an active, malevolent force we can best term “chaos.” In this verse, chaos is envisioned as a dark, undifferentiated mass of water. In 1.9, God creates the dry land (and the seas, which can exist only when water is bounded by dry land). But in 1.1–2.3, water itself and darkness, too, are primordial (contrast Isa. 45.7). In the midrash, Bar Kappara upholds the troubling notion that the Torah shows that God created the world out of preexistent material. But other rabbis worry that acknowledging this would cause people to liken God to a king who had built his palace on a garbage dump, thus arrogantly impugning His majesty (Gen. Rab. 1.5). In the ancient Near East, however, to say that a deity had subdued chaos is to give him the highest praise.

The Jewish Study Bible (Second Edition)

In the beginning of God’s creating the skies and the earth —when the earth had been shapeless and formless, and darkness was on the face of the deep, and God’s spirit was hovering on the face of the water—

Note:

the earth had been: Here is a case in which a tiny point of grammar makes a difference for theology. In the Hebrew of this verse, the noun comes before the verb (in the perfect form). This is now known to be the way of conveying the past perfect in Biblical Hebrew. This point of grammar means that this verse does not mean “the earth was shapeless and formless”—referring to the condition of the earth starting the instant after it was created. This verse rather means that “the earth had been shapeless and formless”—that is, it had already existed in this shapeless condition prior to the creation. Creation of matter in the Torah is not out of nothing (creatio ex nihilo), as many have claimed. And the Torah is not claiming to be telling events from the beginning of time.

shapeless and formless: The two words in the Hebrew, th and bh, are understood to mean virtually the same thing. This is the first appearance in the Torah of a phenomenon in biblical language known as hendiadys, in which two connected words are used to signify one thing. (“Wine and beer” [Lev 10: 9] may be a hendiadys as well, or it may be a merism, a similar construction in which two words are used to signify a totality; so that “wine and beer” means all alcoholic beverages.) The hendiadys of “th and bh,”plus the references to the deep and the water, yields a picture of an undifferentiated, shapeless fluid that had existed prior to creation.

Richard Elliott Friedman, Commentary on the Torah

At the beginning of God’s creating of the heavens and the earth, when the earth was wild and waste, darkness over the face of Ocean,

Note:

At the beginning…: This phrase, which has long been the focus of debate among grammarians, is traditionally read “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.” B-R agrees. I have followed several medieval commentaries, and most moderns, in my rendition.

When the earth…: Gen. 1 describes God’s bringing order out of chaos, not creation from nothingness. Wild and waste: Heb. tohu va-wohu, indicating “emptiness.” Ocean: The primeval waters, a common (and usually divine) image in an ancient Near Eastern mythology.

Everett Fox, The Five Books of Moses

When God was about to create heaven and earth, the earth was a chaos, unformed, and on the chaotic waters’ face there was darkness.

Note:

When God was about to create (b’reishit bara elohim); other translations render this: “In the beginning God created.” Our translation follows Rashi, who said that the first word would have been written (ba-rishonah, at first) if its primary purpose had being to teach the order in which creation took place. Later scholars used the translation “In the beginning” as proof that God created out of nothing (Latin: ex nihilo), but it is not likely that the biblical author was concerned with the question of matter’s origin.

W. Gunther Plaut, The Torah: A Modern Commentary (Revised Edition)

In the beginning when God created the heavens and the earth, the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep, while a wind from God swept over the face of the waters.

Note:

In the beginning when God created, or “When God began to create.” The grammar of this temporal clause was clarified by the medieval Jewish commentator Rashi, who noted that the Hebrew word for “beginning” (reshit) requires a dependent relation—it is the “beginning of” something—and can be followed by a verb. The traditional rendering, “In the beginning, God created,” dates to the Hellenistic period (as in the Septuagint), when these details of classical Hebrew grammar had been forgotten. The idea of creatio ex nihilo (Latin, “creation out of nothing”) is dependent on the later rendering. In the original grammar, creation is a process of ordering and separation that begins with preexisting chaotic matter.

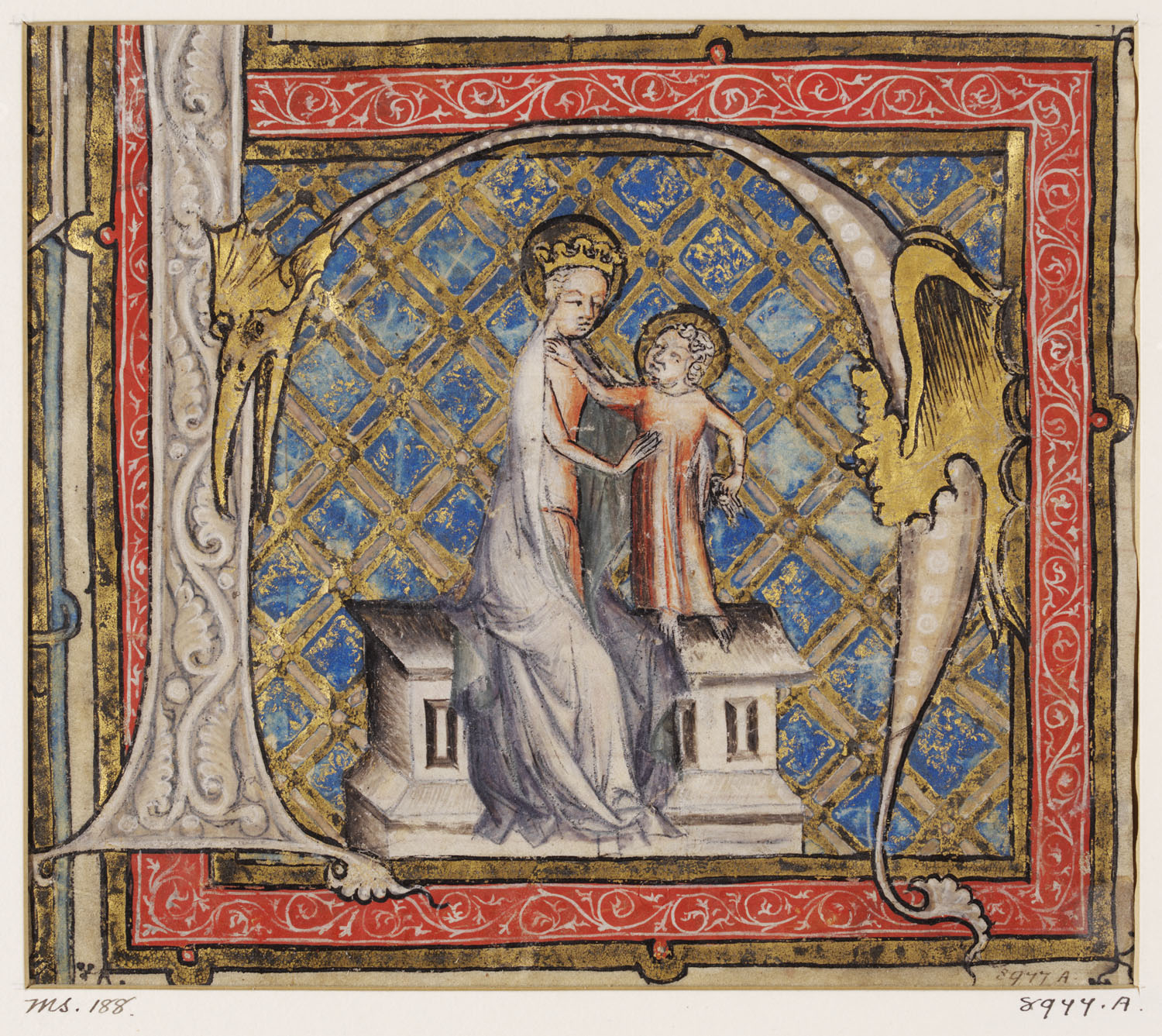

This disjunctive clause portrays the primordial state as a dark, watery chaos, an image similar to the primordial state in Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and Greek traditions. Unlike these other traditions, the chaos here is not a god or gods, but mere matter. The wind from God is he only divine substance and seems to indicate the incipient ordering of this chaos (cf. the role of God’s wind in initiating the reversal of watery chaos in 8.1).

The HarperCollins Study Bible

In the beginning when God created the heavens and the earth, the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep, while a wind from God swept over the face of the waters.

Note:

Scholars differ on whether this verse is to be translated as an independent sentence summarizing what follows (e.g., “In the beginning God created”) or as a temporal phrase describing what things were like when God started (e.g., “When God began to create . . . the earth was a formless void”; cf. 2.4–6). In either case, the text does not describe creation out of nothing (contrast 2 Macc 7.28). Instead, the story emphasizes how God creates order from a watery chaos.

New Oxford Annotated Bible