“Like Jonas himself I find myself traveling toward my destiny in the belly of a paradox.”

Thomas Merton

The Sign of Jonas

The Jewish High Holy Days begins this evening, starting with Rosh Hashanah (New Year 5775) and ending on the tenth day with Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement). So it is a good time to talk about Jonah.

On Yom Kippur, the Book of Jonah is read at services. It is supposedly so simple a story that we tell it to the youngest children. It isn’t that simple.

Prof. Barry Bandstra writes:

The book of Jonah has been interpreted in many different ways: as a satire on prophetic calling and the refusal of prophets to follow God’s call; as a criticism of Israelite prophets who were insincere in preaching repentance (because they really wanted to see destruction); as a criticism of the Jewish community’s unwillingness to respond to prophetic calls to repentance (in contrast with Nineveh); as a criticism of an exclusive view of divine election (God only cares about “chosen people”); as an assertion of God’s freedom to change God’s mind over and against prophets who would limit that freedom; as emphasizing the problem with true and false prophecy (even true prophets have words that do not come true); or as an allegory of Israel in exile (both Jonah and Judah look to God for destruction of an evil empire). De La Torre argues for an interpretation of the book that views Jonah as a marginalized person frustrated with God for not punishing those who have brutally oppressed people. Person reads the book of Jonah as a conversation between author and reader, focusing on the implied verbal rejection of God’s command by Jonah in 1:3.

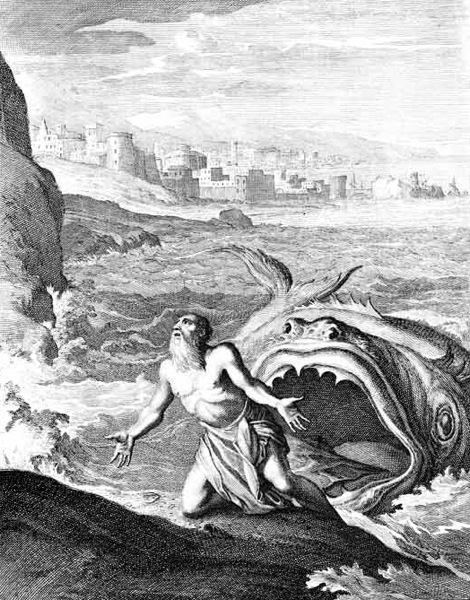

The entire very brief Book of Jonah is at the end of this post. It goes something like this:

God tells Jonah to preach to the wicked city of Nineveh.

Jonah runs away from this assignment and gets on a ship.

A storm batters the ship and the sailors figure out Jonah is the cause.

The sailors say they don’t want to throw him overboard to appease God, but then they do anyway.

Jonah is swallowed by a big fish.

After three days, the fish disgorges Jonah on land.

Jonah finally preaches repentance to Nineveh.

Nineveh does repent.

God has mercy and doesn’t destroy Nineveh.

Jonah complains that he went through a lot of trouble, so God should have destroyed Nineveh.

God gives Jonah a special plant and then destroys it, as an example of how a prophet has nothing to do with what happens and shouldn’t care how God ultimately deals with things. God explains:

“You are concerned for the castor-oil plant which has not cost you any effort and which you did not grow, which came up in a night and has perished in a night. So why should I not be concerned for Nineveh, the great city, in which there are more than a hundred and twenty thousand people who cannot tell their right hand from their left, to say nothing of all the animals?”

So for the New Year, among the many things you may ask yourself:

Was God too lenient? Was Jonah not compassionate enough, taking joy in the misfortune of others? Am I or should I be more like God? Like Jonah? Like the sailors on the ship? Like the people of Nineveh? Like the fish? Can I tell my right hand from my left?

Whatever your faith or no-faith, you can never have enough New Years and new starts. Please have a happy one.

Book of Jonah from the Jerusalem Bible (J.R.R. Tolkien)

Selecting a Catholic translation of the Book of Jonah on Rosh Hashanah may seem odd. There are two reasons. The Jerusalem Bible is the best English-language combination of literary style and scholarship. And this particular book has a very special translator/editor: J.R.R. Tolkien.

The original Jerusalem Bible, published in English in 1966, was conceived as a very modern Catholic Bible—modern in terms of both language and scholarship. A French edition had already been published, and for the English version, a number of English-language scholars and writers were enlisted. Some texts were translated from original languages (Hebrew, Greek) while other texts were re-translations of the French. Tolkien was brought on as an editor, but he did create one book in English, taken from the French: The Book of Jonah.

Jonah 1

1. The word of Yahweh was addressed to Jonah son of Amittai:

2. ‘Up!’ he said, ‘Go to Nineveh, the great city, and proclaim to them that their wickedness has forced itself upon me.’

3. Jonah set about running away from Yahweh, and going to Tarshish. He went down to Jaffa and found a ship bound for Tarshish; he paid his fare and boarded it, to go with them to Tarshish, to get away from Yahweh.

4. But Yahweh threw a hurricane at the sea, and there was such a great storm at sea that the ship threatened to break up.

5. The sailors took fright, and each of them called on his own god, and to lighten the ship they threw the cargo overboard. Jonah, however, had gone below, had lain down in the hold and was fast asleep,

6. when the boatswain went up to him and said, ‘What do you mean by sleeping? Get up! Call on your god! Perhaps he will spare us a thought and not leave us to die.’

7. Then they said to each other, ‘Come on, let us draw lots to find out who is to blame for bringing us this bad luck.’ So they cast lots, and the lot pointed to Jonah.

8. Then they said to him, ‘Tell us, what is your business? Where do you come from? What is your country? What is your nationality?’

9. He replied, ‘I am a Hebrew, and I worship Yahweh, God of Heaven, who made both sea and dry land.’

10. The sailors were seized with terror at this and said, ‘Why ever did you do this?’ since they knew that he was trying to escape from Yahweh, because he had told them so.

11. They then said, ‘What are we to do with you, to make the sea calm down for us?’ For the sea was growing rougher and rougher.

12. He replied, ‘Take me and throw me into the sea, and then it will calm down for you. I know it is my fault that this great storm has struck you.’

13. The sailors rowed hard in an effort to reach the shore, but in vain, since the sea was growing rougher and rougher.

14. So at last they called on Yahweh and said, ‘O, Yahweh, do not let us perish for the sake of this man’s life, and do not hold us responsible for causing an innocent man’s death; for you, Yahweh, have acted as you saw fit.’

15. And taking hold of Jonah they threw him into the sea; and the sea stopped raging.

16. At this, the men were seized with dread of Yahweh; they offered a sacrifice to Yahweh and made vows to him.

Jonah 2

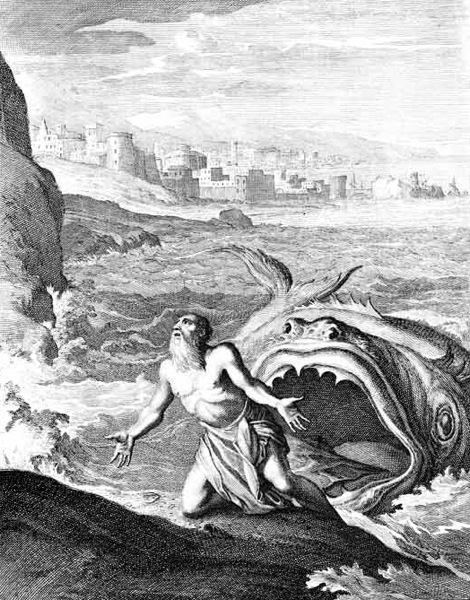

1. Now Yahweh ordained that a great fish should swallow Jonah; and Jonah remained in the belly of the fish for three days and three nights.

2. From the belly of the fish, Jonah prayed to Yahweh, his God; he said:

3. Out of my distress I cried to Yahweh and he answered me, from the belly of Sheol I cried out; you heard my voice!

4. For you threw me into the deep, into the heart of the seas, and the floods closed round me. All your waves and billows passed over me;

5. then I thought, ‘I am banished from your sight; how shall I ever see your holy Temple again?’

6. The waters round me rose to my neck, the deep was closing round me, seaweed twining round my head.

7. To the roots of the mountains, I sank into the underworld, and its bars closed round me for ever. But you raised my life from the Pit, Yahweh my God!

8. When my soul was growing ever weaker, Yahweh, I remembered you, and my prayer reached you in your holy Temple.

9. Some abandon their faithful love by worshipping false gods,

10. but I shall sacrifice to you with songs of praise. The vow I have made I shall fulfil! Salvation comes from Yahweh!

11. Yahweh spoke to the fish, which then vomited Jonah onto the dry land.

Jonah 3

1. The word of Yahweh was addressed to Jonah a second time.

2. ‘Up!’ he said, ‘Go to Nineveh, the great city, and preach to it as I shall tell you.’

3. Jonah set out and went to Nineveh in obedience to the word of Yahweh. Now Nineveh was a city great beyond compare; to cross it took three days.

4. Jonah began by going a day’s journey into the city and then proclaimed, ‘Only forty days more and Nineveh will be overthrown.’

5. And the people of Nineveh believed in God; they proclaimed a fast and put on sackcloth, from the greatest to the least.

6. When the news reached the king of Nineveh, he rose from his throne, took off his robe, put on sackcloth and sat down in ashes.

7. He then had it proclaimed throughout Nineveh, by decree of the king and his nobles, as follows: ‘No person or animal, herd or flock, may eat anything; they may not graze, they may not drink any water.

8. All must put on sackcloth and call on God with all their might; and let everyone renounce his evil ways and violent behaviour.

9. Who knows? Perhaps God will change his mind and relent and renounce his burning wrath, so that we shall not perish.’

10. God saw their efforts to renounce their evil ways. And God relented about the disaster which he had threatened to bring on them, and did not bring it.

Jonah 4

1. This made Jonah very indignant; he fell into a rage.

2. He prayed to Yahweh and said, ‘Please, Yahweh, isn’t this what I said would happen when I was still in my own country? That was why I first tried to flee to Tarshish, since I knew you were a tender, compassionate God, slow to anger, rich in faithful love, who relents about inflicting disaster.

3. So now, Yahweh, please take my life, for I might as well be dead as go on living.’

4. Yahweh replied, ‘Are you right to be angry?’

5. Jonah then left the city and sat down to the east of the city. There he made himself a shelter and sat under it in the shade, to see what would happen to the city.

6. Yahweh God then ordained that a castor-oil plant should grow up over Jonah to give shade for his head and soothe his ill-humour; Jonah was delighted with the castor-oil plant.

7. But at dawn the next day, God ordained that a worm should attack the castor-oil plant — and it withered.

8. Next, when the sun rose, God ordained that there should be a scorching east wind; the sun beat down so hard on Jonah’s head that he was overcome and begged for death, saying, ‘I might as well be dead as go on living.’

9. God said to Jonah, ‘Are you right to be angry about the castor-oil plant?’ He replied, ‘I have every right to be angry, mortally angry!’

10. Yahweh replied, ‘You are concerned for the castor-oil plant which has not cost you any effort and which you did not grow, which came up in a night and has perished in a night.

11. So why should I not be concerned for Nineveh, the great city, in which there are more than a hundred and twenty thousand people who cannot tell their right hand from their left, to say nothing of all the animals?’