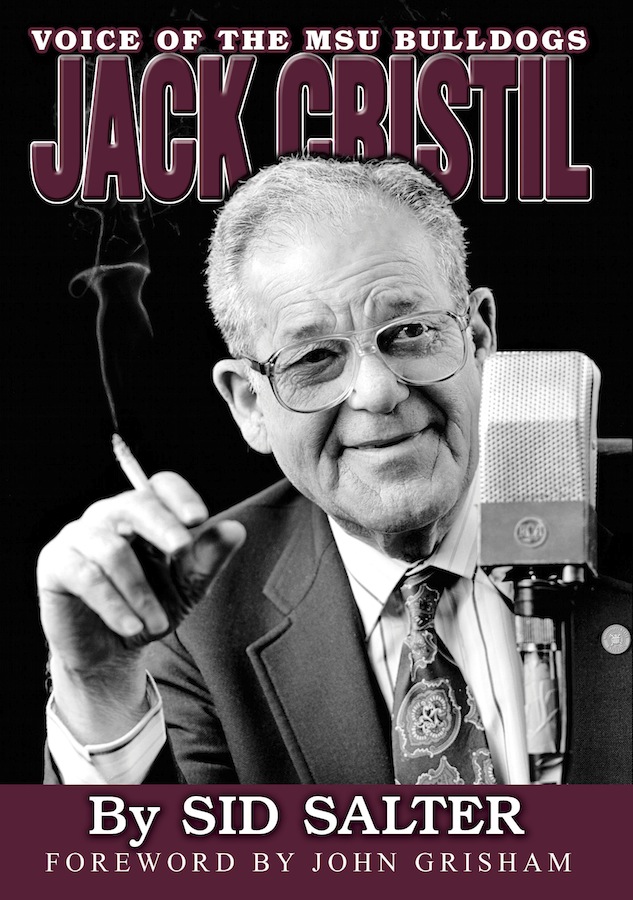

Radio: Rosko

”When are we going to learn that controlling something does not take it out of the minds of people?”

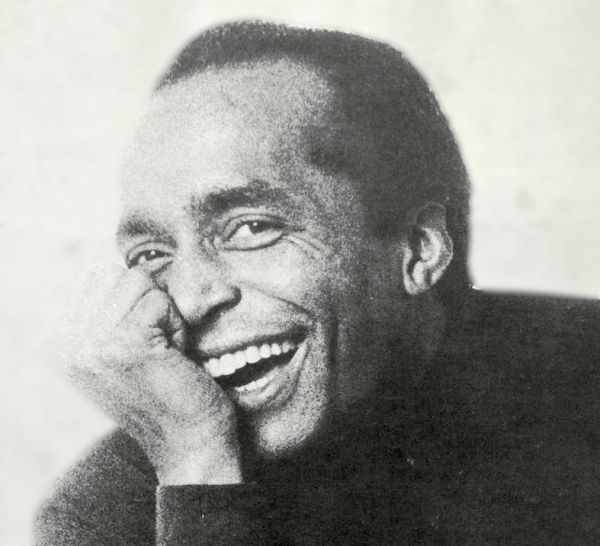

Rosko

I was going to write today about radio. How it was a social medium for a generation, how formative it was for me.

I listened today to recordings of radio shows and personalities that I listened to growing up in New York, first thing in the morning to last thing doing homework and falling asleep. Today I touched base with some of the radio stations (found at http://www.nyradioarchive.com).

One standout station was WNEW-FM. In the late 1960s, it reformed from mainstream music to progressive anything and everything. The station personalities changed too. Among them was Alison Steele, the Nightbird. And then there was Rosko.

It wasn’t just Rosko’s inimitable voice at night. It was his sensibility, musical and otherwise. As the New York Times obituary below reflects.

Listen to an hour of Rosko from November 27, 1967. If this is distant history for you, listen without prejudice, and you will hear great music and a radically humane radio personality.

Rosko Is Dead

By Jon Pareles

New York Times

Aug. 6, 2000

William Roscoe Mercer, known for decades to New York radio listeners simply as Rosko, died on Tuesday. He was 73 and lived in New York.

The cause was cancer, according to his daughter Valerie J. Mercer.

Mr. Mercer was the first black news announcer on WINS in New York and, as Rosko, the first black disc jockey on KBLA in Los Angeles. He went on to become a pioneer of free-form FM radio in New York City. On WOR-FM in 1966 and on WNEW-FM from 1967 to 1970, his calm, husky voice with its hint of Southern drawl and his wide-ranging programming made him an authoritative companion amid the musical ferment of the late 1960’s.

He delved into rock, soul, folk and jazz; he read poetry and conversed with his unseen listeners in almost fatherly monologues. In one set during the late 1960’s, he recited antiwar poetry by Yevgeny Yevtushenko to the Mormon Tabernacle Choir singing the Lord’s Prayer, then played Richie Havens’s antiwar song ”Handsome Johnny” as a lead-in to a news report about bombing in Vietnam.

Mr. Mercer was born on May 25, 1927, in New York City and attended a Catholic boarding school in Pennsylvania as a charity student. His first jobs were as a government clerk and then a men’s-room attendant at the Latin Casino in Cherry Hill, N.J. He began his radio career as a jazz disc jockey at WHAT in Chester, Pa., moved to WDAS in Philadelphia, and then to WBLS in New York, playing jazz in live broadcasts from Palm Cafe in Manhattan. He played rhythm-and-blues on WNJR in Secaucus, N.J., in the late 1950’s, but after refusing to cross a picket line at the station during an effort to create a union for disc jockeys, he was blacklisted for six months.

He became the first black announcer for WINS, and was then hired as a disc jockey by KDIA in Oakland, Calif. Radio station KGFJ in Los Angeles sought to hire him away, leading to a precedent-setting lawsuit that changed the way disc-jockey contracts were written. For a time in the early 1960’s, Rosko was heard live on KGFJ and on tape in Oakland six nights a week; he spent the seventh in Oakland, live on KDIA. Then he was hired by KBLA, playing rock and rhythm-and-blues at a formerly all-white station.

He returned to New York to work at WBLS. In 1966, the Federal Communications Commission required radio stations to broadcast separate content on AM and FM stations, and rock music beyond the Top 40 rushed to fill the new air time. The disc jockeys Murray the K and Scott Muni, along with Rosko, moved to WOR-FM to introduce a new style, with disc jockeys freely choosing the music and speaking conversationally to listeners.

But in October 1967, WOR-FM decided to change to a restrictive format. On his last show, without warning the station’s management, Rosko spoke for five minutes about why he was resigning, saying, ”When are we going to learn that controlling something does not take it out of the minds of people?” and declaring, ”In no way can I feel that I can continue my radio career by being dishonest with you.” He added that he would rather return to being a men’s-room attendant.

But within the month, he was hired for an evening shift by WNEW-FM, which picked up WOR-FM’s format; soon afterward, WNEW-FM also hired Mr. Muni. Rosko stayed at WNEW until 1970, then moved to France for five years; there, he worked for the Voice of America. He returned to the United States and was heard during the 1980’s on the dance-music station WKTU in New York; he also did voice-over work for commercials. Most recently, his voice was heard in announcements for CBS Sports. In 1992, when he learned he had cancer, he refused chemotherapy, turning instead to alternative medicine.