Don’t forget Gaza

One crisis after another.

Greenland. Venezuela. Minneapolis. It is easy to forget any particular crisis. Or put another way, it is impossible to pay attention to all the crises. Not to mention all the non-critical items that crop up in our lives and our vision, some pleasant, some not.

So when one crisis gets mentioned or covered, there may be a tendency to say “well, what about…?”

So here I am saying, “What about Gaza?” That is, despite all the other headlines, don’t forget Gaza.

As I’ve implied before, in posts and conversations, Israel, including the Gaza situation, is all about theology, particularly Old Testament theology.

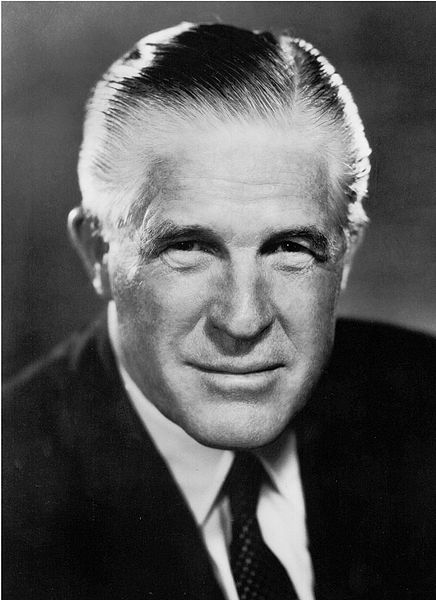

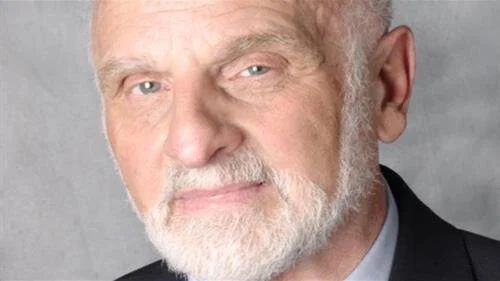

Walter Brueggemann (1933-2025) was one of the most prolific and influential theologians of the 20th and 21st centuries. Much of his work focused on the Old Testament, in which he found radical guidance for modern people of faith—a Bible that does not demand, justify or accept damaging political ideologies and nationalism.

In 2015 Brueggemann published Chosen?: Reading the Bible Amid the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. He wrote:

INTRODUCTION

The seemingly insolvable conflict between the state of Israel and the Palestinian people requires our best thinking, our steadfast courage, and a deep honesty about the politically possible. The conflict is only “seemingly” beyond solution, because all historical-political problems have solutions if there is enough courage, honesty, and steadfastness.

The conflict is not a fixed, unchanging situation; rather, it is a dynamic historical reality that is dramatically changing and being redefined over time. As a result, it is imperative that our thinking not be settled in a fixed position but that it be regularly reevaluated in response to the changed and changing realities on the ground. If we should settle for a fixed solution, then we will have arrived at an ideology, which is quite unhelpful for real problems on the ground.

In my own thinking, which is much influenced by my work as a Scripture scholar, I begin with a focus on the claim of Israel as God’s chosen people. That conviction is not in doubt in the Bible. It is a theological claim, moreover, that fits with compelling persuasiveness with the reality of Jews in the wake of World War II and the Shoah. Jews were indeed a vulnerable people whose requirement of a homeland was an overriding urgency. Like many Christians, progressive and evangelical, I was grateful (and continue to be so) for the founding and prospering of the state of Israel as an embodiment of God’s chosen people. That much is expressed in my earlier book entitled The Land. I took “the holy land” to be the appropriate place for the chosen people of the Bible which anticipates the well-being of Israel that takes land and people together.

Of course, much has changed since then in the linkage between the state of Israel and the destiny of the chosen people of God.

–The state of Israel has evolved into an immense military power, presumably with a nuclear capacity. There is no doubt that such an insistence on military power has been in part evoked by a hostile environment in which the state of Israel lives, including periodic attacks by neighboring states.

–The state of Israel has escalated (and continues to escalate) its occupation of the West Bank by an aggressive development of new settlements.

–The state of Israel has exhibited a massive indifference to the human rights of Palestinians.

Thus, it seems to me that the state of Israel, in its present inclination and strategy, cannot expect much “positive play” from its identity as “God’s chosen people.” As a consequence, my own judgment is that important initiatives must be taken to secure the human rights of Palestinians. This changed stance on my part is reflected in the new edition of my book on the land. It is a change, moreover, that is featured in the thinking of many critics who have been and continue to be fully committed to the security of the state of Israel, as am I.

This rethinking is important both for political reasons and for more fundamental interpretive issues. A change in attitude and policy is important to help resolve the conflict. It is clear enough that the state of Israel will continue to show little restraint in its actions toward Palestinians as long as U.S. policy gives it a “blank check” along with commensurate financial backing. Such one-sided and unconditional support for the state of Israel is not finally in the interest of any party, for peace will come only with the legitimation of the political reality of both Israelis and Palestinians. As long as this issue remains unaddressed, destabilization will continue to be a threat to the larger region.

It will not do for Christian readers of the Bible to reduce the Bible to an ideological prop for the state of Israel, as though support for Israel were a final outcome of biblical testimony. The dynamism of the Bible, with its complex interactions of the chosen people and other peoples, is fully attested, and we do well to see what is going on in the Bible itself that is complex and cannot be reduced to a simplistic defense of chosenness. The Bible itself knows better than that!

It is my hope that the Christian community in the United States will cease to appeal to the Bible as a direct support for the state of Israel and will have the courage to deal with the political realities without being cowed by accusations of anti-Semitism.

It is my further hope that U.S. Christians will become more vigorous advocates for human rights and will urge the U.S. government to back away from a one-dimensional ideology for the sake of political realism. It seems to many of us that the so-called two-state solution is a dead possibility, as Israel in its present stance will never permit a viable Palestinian state. We are required to do fresh thinking about human rights in the face of the capacity for power coupled with indifference and cynicism in the policies of the state of Israel, which is regularly immune to any concern for human rights.

I have not changed my mind an iota about the status of Israel as God’s chosen people or about urgency for the security and well-being of the state of Israel. Certainly the Christian West continues to have much to answer for with its history of anti-Semitic attitudes and policies. None of that legacy, however, ought to cause blindness or indifference to political reality and the way in which uncriticized ideology does enormous damage to prospects for peace and for the hopes and historical possibilities of the vulnerable. The attempt to frame the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in terms of anti-Semitism is unpersuasive. More courage and honesty are required amid the realities of human domination and human suffering. As the hymn writer James Russell Lowell wrote in reference to the U.S. Civil War, “New occasions teach new duties.” The current conflict, with its escalation of cynical violence, is a new occasion. New duties are now required.

Walter Brueggemann, Chosen?: Reading the Bible Amid the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict