Missing the way by a hairbreadth

is the gap between heaven and earth.

Xinxin Ming (Verses on the Faith Mind), Jianzhi Sengcan (d. 606)

When I saw the following in The Wall Street Journal, I was dumbfounded.

Competitive About Your Meditation? Relax, Everyone Else is Too

As hard-chargers descend on the ancient practice, they are tweaking the quest for inner peace

By Ellen Gamerman

Alan Stein Jr. is on his 324th straight day meditating—a streak he is tending with the mindfulness of a monk.

The 42-year-old performance coach from Gaithersburg, Md., has kept his record using the Headspace app, despite early-morning flights and travel across time zones. On a recent work trip to Atlanta, he remembered to meditate only just after the clock struck midnight. Worried he’d blown his record, he closed his eyes and quickly tried to meditate on the hotel bed for 10 minutes.

“The whole time I’m just waiting for the 10 minutes to be over to see if my streak was alive,” he said. …

Desperate to maintain streaks that can surpass 1,000 days, some driven spiritual voyagers have started looking for new ways to protect their records. On Headspace, the app counts any session completed in an eight-hour period as its own day. Pointing this out, a user on Facebook suggested logging three days in one by meditating at 4 a.m., 2 p.m. and 11 p.m.

On Mindful Makers, a private online group of roughly 250 meditators, members can check the streak rankings daily. Robin Koppensteiner was in second place with 71 days at the start of this week. Members are trusted to report their own meditation updates.

“I have to admit I check every day to see if I’m still in number two or if I’ve gone up to number one,” said the 29-year-old author from Vienna, Austria.

As astonishing as this seems, it should not be surprising.

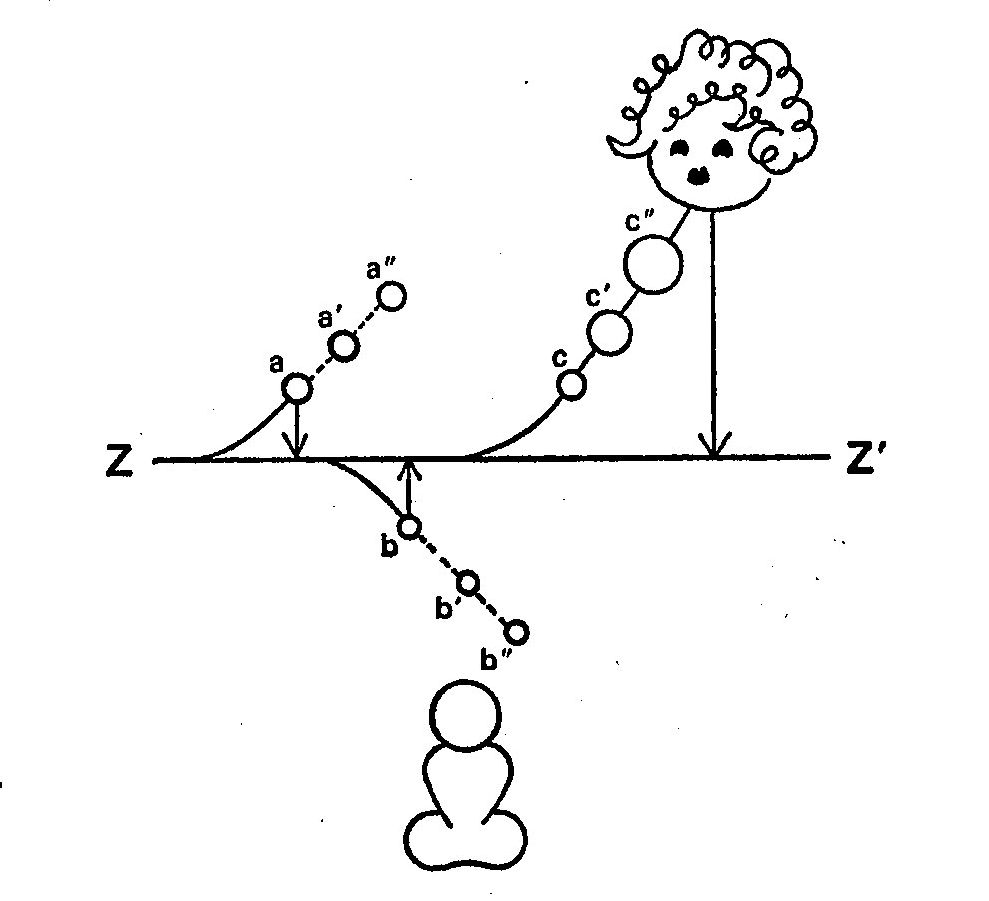

Every tradition that includes meditation as a practice warns practitioners of objectifying the practice itself, rather than experiencing the practice only for what it is within a bigger context. This is a danger inherent in all religious and spiritual traditions, where specific practices seem to overtake the bigger point. As the Zen saying goes, it is confusing the finger pointing at the moon for the moon itself.

Chogyam Trungpa called this spiritual materialism, which is a central idea in his classic Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism: “The problem is that ego can convert anything to its own use, even spirituality.”

Now in the case of many of these meditators, they are pursuing calm, relaxation or peace of mind, rather than following any particular way, Buddhist or otherwise. Which is fine. But the advantage of practicing within a bigger context is that you are regularly reminded and discover for yourself that things like “meditation streaks” are kind of ridiculous and kind of misleading. In fact, the meditation session you miss might be the very session the brings you the calm, relaxation and peace of mind you are seeking. If you are a “competitive meditator” that will mean nothing to you. If you are, for example, a Zen practitioner, it makes perfect sense.

For meditators worried about breaking their streak and losing the meditation competition, this from Suzuki Roshi:

One of my students wrote to me saying, “You sent me a calendar, and I am trying to follow the good mottoes which appear on each page. But the year has hardly begun, and already I have failed!” Dogen-zenji said, “Shoshaku jushaku.” Shaku generally means “mistake” or “wrong.” Shoshaku jushaku means “to succeed wrong with wrong,” or one continuous mistake. According to Dogen, one continuous mistake can also be Zen. A Zen master’s life could be said to be so many years of shoshaku jushaku. This means so many years of one single-minded effort.