In Jewish congregations, the annual Torah reading cycle begins again this week with the first chapters of the Bible. In Hebrew it begins with the word b’reishit, and in its best-known translation, the first verse goes like this:

In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth.

And with that comes a puzzle.

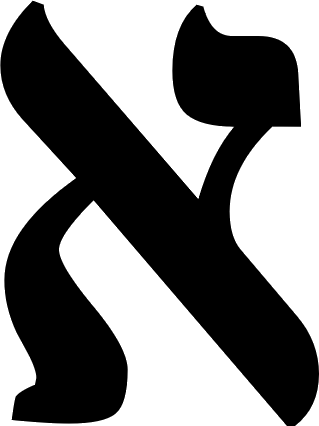

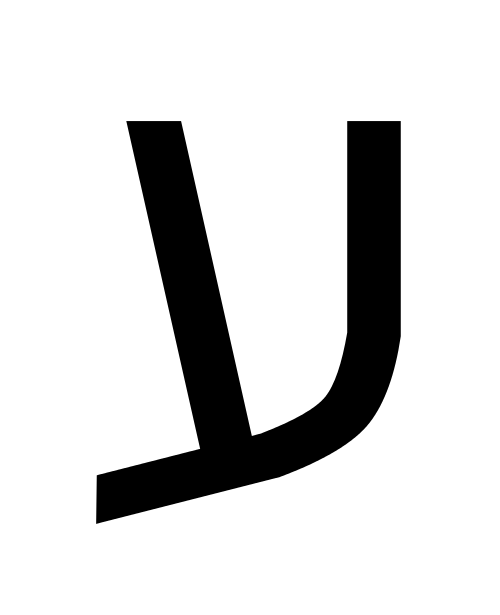

If B’reishit is the beginning of a very big and consequential story, and if the creators of the Torah were sensitive to the mystical meanings of the Hebrew alphabet and language, why does the Torah begin with the second letter bet (B) rather than the first letter alef (A)?

Looking at a bigger picture, this connects to a related puzzle and an unlikely source: the I Ching.

The I Ching is a classic of Chinese literature and philosophy, a text as ancient as the Torah and just as influential.

Richard J. Smith writes in The I Ching: A Biography:

The Changes first took shape about three thousand years ago as a divination manual, consisting of sixty-four six-line symbols known as hexagrams. Each hexagram was uniquely constructed, distinguished from all the others by its combination of solid (——) and/or broken (— —) lines. The first two hexagrams in the conventional order are Qian and Kun; the remaining sixty-two hexagrams represent permutations of these two paradigmatic symbols….

The operating assumption of the Changes, as it developed over time, was that these hexagrams represented the basic circumstances of change in the universe, and that by selecting a particular hexagram or hexagrams and correctly interpreting the various symbolic elements of each, a person could gain insight into the patterns of cosmic change and devise a strategy for dealing with problems or uncertainties concerning the present and the future.

The first intriguing note is that the I Ching (pronounced Yi Jing) begins with those hexagrams Qian and Kun—known generally in English as Heaven and Earth. The cosmos of change and the I Ching begin then with Heaven and Earth.

It is at the close of the 64 hexagrams that the conundrum appears. Hexagram 63, the penultimate one, is Ji Ji—After Completion. This should be the end of the story. But it isn’t. The final hexagram, Hexagram 64, is Wei Jei—Before Completion. In the end, it doesn’t stop. It begins again. The Book of Changes emphasizes that the changes never end.

This is an explanation of why the Torah does not begin with the beginning of the alphabet. If it starts with A, that presumes a Z, A to Z, or in Hebrew, alef to tav. Creation would thus be represented as a finite element of a finite cosmos. In the text it starts instead, as the Latin phrase goes, in media res—in the middle of things. Just as the Torah will end in the middle of things, after completion of a journey, but with Moses never allowed to experience what is yet to happen, before the next completion. On and on, always beginning, never done. Just like the I Ching. Just like the Torah itself.