Which Comes First: Evolution or Revolution?

The 20th century gave us two world wars and an atomic bomb, but the most interesting of the Big Events of the century may be the Russian Revolution. An inequitable and unbalanced way of life gave bloody way to abstract enlightened visions of a better world. The particular inequities ended, Russia moved into modern times, but competition for the “right” vision and ineradicable baser human natures seeking power and control led to decades of national and global troubles. “Meet the new boss, same as the old boss,” the Who said.

The Russian Revolution was grounded in a Marxist vision, which was in turn a Christian vision: a community on earth as it is in heaven, a brotherhood of people in which suffering and want would be softened, if not alleviated, by those who have a surplus of comfort and resource. It was Lennon, not Marx, who said, “You can say I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one. I hope someday you’ll join us, and the world will live as one.”

What went wrong?

What almost always goes wrong is that evolution and revolution are out of sync. It is easy to say that people and society should first evolve for a while, and then at some critical moment, all that’s needed is that next faster-than-evolution event to take it to the next level.

That turns out rarely to be the case.

Evolution is slow, erratic, and always engenders resistance and reaction. The cliché is that people and society fear change, but that is too easy. They fear the unknown. The expression “better the devil you know than the one you don’t” sums it up. It takes a substantial leap—you might say a leap of faith—the walk into a vision rather than remain in a lesser but familiar reality.

Revolution is both an attempt to make evolution more real and to create conditions where that evolution can continue more broadly and forcefully. But, as pointed out with the Russian experience, it doesn’t always work that way. Revolution is conflict, and conflict creates its own set of conditions sometimes antithetical to evolution. “Fighting for peace” is oxymoronic (some would say just plain moronic), but we have had to live through that. (Note the moment in Stanley Kubrick’s brilliant film Dr. Strangelove where the President scolds his arguing advisers, “Stop it. There’s no fighting in the War Room.”)

One of the exceptional examples of evolution and revolution working together is the American Revolution. It is one of the reasons it worked so well. The founders may have been the fathers of our country, but they were the children of the Enlightenment. That multi-faceted evolution—philosophical, political, economic, spiritual—had gone as far as it could go when it hit a wall. They believed that if they could break through, which did mean war, they could establish an enlightened nation. And, to an extent greater or lesser than some might like or expect, they did.

Evolution, or lack of it, is at the heart of some current American problems.

America is heir to two great evolutions, sometimes unrecognized, often distorted. Some of those obstructionists who fight today hark back to the patriots who were mad as hell and wouldn’t take it any more, and so upended a cargo of British tea. Others who claim this is a Christian nation have the idea that if alive today, Jesus would certainly choose to be an American.

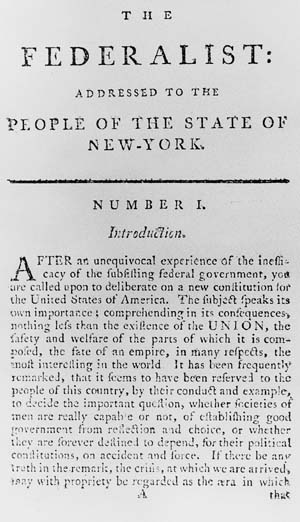

Every American in these dynamic times is free to pick the evolution they aspire to. There are plenty to choose from. We do have two very big ones on the menu. If a rabid revolutionary patriot, you might choose to follow the path of a 21st century version of Enlightenment; you might even study the work of those founding Enlightenists—Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, et al.—for guidance. If a committed Christian it’s even easier. No slogging through the Federalist Papers, or even the whole Bible. Just read and read again the words of Jesus—the ones in red type—and consider just how much evolution he was asking for and expecting. Then again, maybe it’s not evolution he was talking about at all.