The relationship between American society and Islam is complicated.

At this point in history, there are few sentences that could be more absurdly understated. In so many spheres, that relationship is, to be polite, messed up beyond all reason.

There is a long and growing list of events and phenomena that contribute to and reflect those complications. How the world’s largest or second-largest religion (depending on accounting) became so toxic in the world’s most tolerant democracy is a story still being written. No doubt having a black President whose father was a Muslim, who spent part of his youth in the world’s most Muslim country, and whose middle name is Hussein is the latest part of that.

The Postal Service, out of a sense of decency and diversity and political realities, rushes in where others fear to tread. This is itself a complicated thing.

October 26 is Eid al-Adha (“Feast of the Sacrifice”), the major holiday on the Muslim calendar.

Islam shares many stories with its Abrahamic precursors, Judaism and Christianity, though some of the scripture is added to or modified. So it is with the story of Ibrahim (Abraham) and his son Ishmael (Isaac). Ibrahim and Ishmael are said to have built the Kaaba, the building in Mecca that is the centerpiece of the commanded pilgrimage—the hajj. Ibrahim was also told in a dream to sacrifice his son as a sign of obedience to Allah and, as in the Old Testament, was stopped only at the last moment when Ishmael was replaced by a sacrificial sheep.

Eid al-Adha marks the end of the annual pilgrimage and Ibrahim’s faithful near-sacrifice of his son. (For discussion elsewhere, the question of how this deep and fascinating father-son sacrifice in the Old Testament—see, e.g., Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling—is not on the Jewish calendar, but became such a central event of the Christian and Muslim calendars.)

Some think that the Postal Service should not be in the business of commemorating religious holidays and people, given the wall—the admittedly porous wall—between church and state. The Mother Teresa stamp issued in 2010 is just one of those flash points. The Postal Service explains:

Following the announcement of the Mother Teresa stamp, groups such as the Freedom from Religion Foundation objected to the Postal Service’s seeming violation of its own guidelines.

“We received numerous letters saying that we should not be doing religious stamps,” says Terry McCaffrey, manager of stamp development. “But we are honoring her for her humanitarian work, not for being a member of a religious order.”

After all, McCaffrey asks, to what extent should religious inspiration disqualify an otherwise worthy subject?

Over the years, many religious figures have been depicted on stamps in recognition of their contributions to society, independent of their personal motivations or beliefs. Stamp honorees have included Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., for leading the struggle for civil rights, Father Edward Joseph Flanagan for his work with delinquent and homeless boys, and Padre Félix Varela for his advocacy for the immigrant poor.

Still, the signs of protest for Mother Teresa were stronger than with most stamps.

As for minority religions, the Postal Service shies away (but see Hanukkah below). No Buddhism, for example. Interestingly and somewhat surprisingly, the Postal Service did dip its toe in Mormon waters. In December 2005, it gave a nod to the 200th anniversary of Joseph Smith’s birth, not with a stamp, but with the much less substantial cancellation mark. Note below that the Postal Service did not issue this postcard; that is privately produced. The only government involvement is the cancellation mark. Also notable is that given it was holiday season, this postcard includes a Madonna stamp to go along with the Joseph Smith cancellation.

Holidays provide a little bit of cover for the Postal Service. Instead of unacceptably eliminating Christmas, the Postal Service went to religious inclusiveness and diversity. So we have a Hanukkah stamp for Judaism—even though Hannukah is a relatively minor holiday on the Jewish calendar.

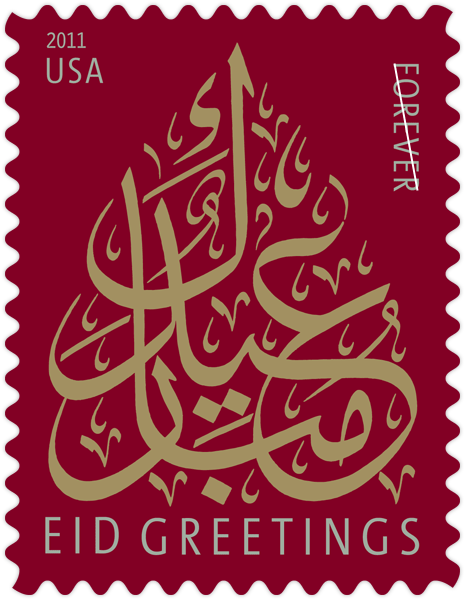

A few years ago, we were offered a Muslim stamp for the Eid feasts:

This stamp commemorates the two most important festivals — or eids — in the Islamic calendar: Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha, and features the Arabic phrase “Eid mubarak” in gold calligraphy on a blue background. Eid mubarak translates literally as “blessed festival,” and can be paraphrased “May your religious holiday be blessed.”

Employing traditional methods and instruments to create this design, calligrapher Mohamed Zakariya of Arlington, VA, working under the direction of Phil Jordan of Falls Church, VA, chose a script known in Arabic as “thuluth” and in Turkish as “sulus.”

As shown above, the Postal Service modified the Eid stamp in 2011, keeping the exquisite calligraphy, changing the color from blue to red, and issuing it as a Forever® stamp:

The U.S. Postal Service® commemorates the two most important festivals — or eids — in the Islamic calendar: Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha. On these days, Muslims wish each other Eid Mubarak, the phrase shown in calligraphy on the stamp. Eid Mubarak translates literally as “blessed festival” and can be paraphrased “May your religious holiday be blessed.” This Eid stamp features gold calligraphy against a reddish background.

Saying that the original Eid stamp was issued “a few years ago” is imprecise. It was actually issued on September 1, 2001—ten days before 9/11. It seems that this small step in the direction of recognition and tolerance got lost in some twisted history that as a country we are still trying to straighten out.

The stamp is available for purchase from the Postal Service. And even if you are not among the 1.7 billion people celebrating Eid al-Adha next week, it is still a beautiful addition to any piece of mail—and a beautiful statement.