Even if you are not interested in Zen or Buddhism, this is your invitation to discover one of the most fascinating and overlooked figures in 20th century religion.

If you are a student of Zen, and think you have a broad overview of Zen in the last century, you may wonder why you’ve never heard of Kodo Sawaki Roshi (1880-1965), let alone read any of his work. Up to now, circumstances worked against that. But that has changed with the just-published The Zen Teaching of Homeless Kodo from Wisdom Publications. You owe it to yourself to fill that gap.

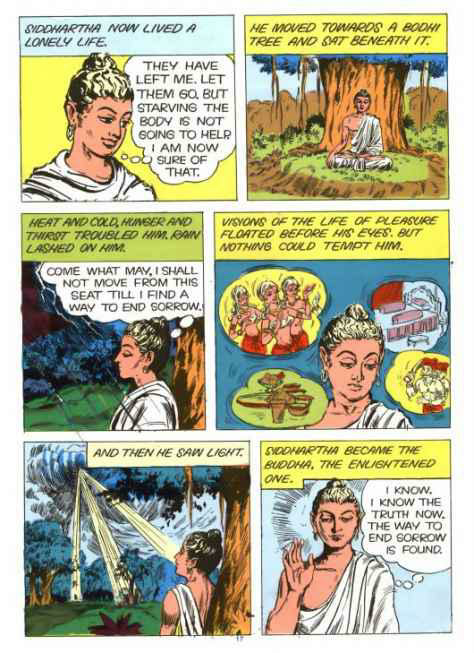

Lineage is an essential element of Zen, a tracing of the conceptual DNA that reaches back to Bodhidharma, who in the 5th or 6th century BCE legendarily brought Buddhism from India to China. Thus begins the story of Chinese Ch’an (later Japanese Zen) Buddhism.

In the modern Western incarnations of Zen, some lineages are well-known. Arguably the most popular of all teachers in the West is Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, who founded the San Francisco Zen Center. The first collection of his teachings, Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, remains the bestselling introduction to Zen practice in English. It is clear and captivating, and it captured many, including me years ago.

Maybe not as well-known, but equally important, is the work of Kosho Uchiyama Roshi. Published at about the same time as Zen Mind, Uchiyama Roshi’s Approach to Zen lacked the design and print sophistication of Suzuki’s book. Instead of Zen Mind’s colorful cover, calligraphy, and fine typesetting, Approach to Zen is plain brown, with simple illustrations hand-drawn by Uchiyama Roshi.

Proving that you can’t judge a book by its cover or color, Approach to Zen is an excellent primer on practice and philosophy. It was later expanded into the even more valuable Opening the Hand of Thought: Foundations of Zen Buddhist Practice (where happily a few of the original drawings are kept). If you are Zen-curious, you could do no better than starting with the pair of Zen Mind and Opening the Hand of Thought.

Sawaki Roshi was Uchiyama Roshi’s teacher. Uchiyama Roshi’s best-known student is Shohaku Okumura, whose practice includes being one of the premier translators of Zen texts—now including the work of Sawaki Roshi. In this new book, these three teachers, three points on an extraordinary line, come together.

Zen masters often have complex lives, but more than most, Sawaki Roshi’s story defies quick summary. The emblematic thing to know about his life and teaching is that he was an iconoclast. It is conventional for great teachers to take over a temple, so that they can effectively (and perhaps comfortably) transmit their teachings. Sawaki refused that possibility; he was, as a teacher for decades, without a home.

People call me Homeless Kodo, but I don’t think they particularly intend to disparage me. They say “homeless” probably because I never had a temple or owned a house. Anyway, all human beings without exception are in reality homeless. It’s a mistake to think we have a solid home.

Zen is renowned for straight talk, even when that talk seems to be crooked, wandering around so that the undeniable point remains out of easy reach or reason. In these excerpts, Kodo Sawaki employs the straightest of straight talk—no less philosophically deep than the most puzzling of messages, but as punishing and sometimes sarcastic as a punch in the face.

When people are alone, they’re not so bad. However, when a group forms, paralysis occurs; people become totally foolish and cannot distinguish good from bad. Their minds are numbed by the group. Because of their desire to belong and even to lose themselves, some pay membership fees. Others work on advertising to attract people and intoxicate them for some political, spiritual, or commercial purpose.

I keep some distance from society, not to escape it but to avoid this kind of paralysis. To practice zazen is to become free of this group stupidity.

Some opinions have passed their prime and lost relevance. For instance, when grownups lecture children, they often simply repeat ready-made opinions. They merely say, “Good is good; bad is bad.” When greens go to seed, they become hard and fibrous. They aren’t edible anymore. We should always see things with fresh eyes!

Often people say, “This is valuable!” But what’s really valuable? Nothing. When you die, you have to leave everything behind. Even the national treasures in Kyoto and Nara will sooner or later perish. It’s not a problem even if they all burn down.

Equal to the value of these teachings is the layering of commentary on Sawaki Roshi by his student Uchiyama Roshi and by Uchiyama Roshi’s student Shohaku Okumura. Layered commentary is common not only to Zen, but to many religious and philosophical traditions. Yet this is remarkable for combining erudite exposition about the teachings and Zen with what can only be described as filial respect and affection—that is, love. Though two of the three participants have died, you feel as if you are present for an enlightened three-way conversation among grandfather, father, and son.

You will wish that it would never end. In a sense, it never does or has to. You can take the treasures you find here and incorporate them into your life, your thinking, and, if you are inclined that way, into your practice.

A horse and a cat once discussed the question, “What is happiness?” They couldn’t reach any agreement.