“No one today can afford to be innocent, or indulge himself in ignorance of the nature of contemporary governments, politics and social orders. The national polities of the modern world maintain their existence by deliberately fostered craving and fear: monstrous protection rackets.”

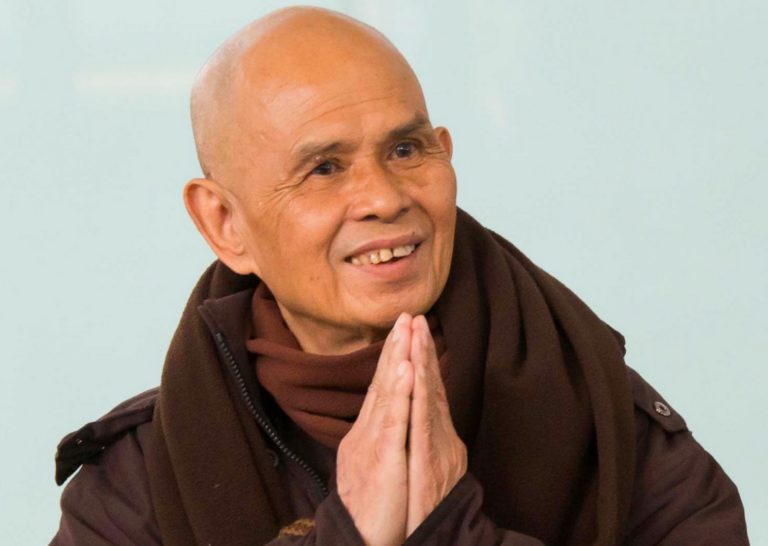

Celebrated poet Gary Snyder has been a master swimmer in the cultural and spiritual currents of our times. His biography from the Poetry Foundation notes:

Gary Snyder began his career in the 1950s as a noted member of the “Beat Generation,” though he has since explored a wide range of social and spiritual matters in both poetry and prose. Snyder’s work blends physical reality and precise observations of nature with inner insight received primarily through the practice of Zen Buddhism. While Snyder has gained attention as a spokesman for the preservation of the natural world and its earth-conscious cultures, he is not simply a “back-to-nature” poet with a facile message….

Snyder’s emphasis on metaphysics and his celebration of the natural order remove his work from the general tenor of Beat writing—and in fact Snyder is also identified as a poet of the San Francisco Renaissance along with Jack Spicer, Robert Duncan and Robin Blaser. Snyder has looked to the Orient and to the beliefs of American Indians for positive responses to the world, and he has tempered his studies with stints of hard physical labor as a logger and trail builder. Altieri believed that Snyder’s “articulation of a possible religious faith” independent of Western culture has greatly enhanced his popularity. In his study of the poet, Bob Steuding described how Snyder’s accessible style, drawn from the examples of Japanese haiku and Chinese verse, “has created a new kind of poetry that is direct, concrete, non-Romantic, and ecological. . . . Snyder’s work will be remembered in its own right as the example of a new direction taken in American literature.” Nation contributor Richard Tillinghast wrote: “In Snyder the stuff of the world ‘content’—has always shone with a wonderful sense of earthiness and health. He has always had things to tell us, experiences to relate, a set of values to expound. . . . He has influenced a generation.”

In 1961, Snyder published an essay entitled Buddhist Anarchism. Anarchism is a slippery term, though a call to turn things upside down, or an observation of our heading there, probably qualifies. The Buddhist part is definite here. Yes, it is radical, and pragmatic history may seem to demonstrate that the vision is idealistic, impractical and impossible. Even quaint in the face of the 21st century real world and real life. But without the idealistic, impractical and impossible, where is the fun and the future?

BUDDHIST ANARCHISM

Buddhism holds that the universe and all creatures in it are intrinsically in a state of complete wisdom, love and compassion; acting in natural response and mutual interdependence. The personal realization of this from-the-beginning state cannot be had for and by one-“self” — because it is not fully realized unless one has given the self up; and away.

In the Buddhist view, that which obstructs the effortless manifestation of this is Ignorance, which projects into fear and needless craving. Historically, Buddhist philosophers have failed to analyze out the degree to which ignorance and suffering are caused or encouraged by social factors, considering fear-and-desire to be given facts of the human condition. Consequently the major concern of Buddhist philosophy is epistemology and “psychology” with no attention paid to historical or sociological problems. Although Mahayana Buddhism has a grand vision of universal salvation, the actual achievement of Buddhism has been the development of practical systems of meditation toward the end of liberating a few dedicated individuals from psychological hangups and cultural conditionings. Institutional Buddhism has been conspicuously ready to accept or ignore the inequalities and tyrannies of whatever political system it found itself under. This can be death to Buddhism, because it is death to any meaningful function of compassion. Wisdom without compassion feels no pain.

No one today can afford to be innocent, or indulge himself in ignorance of the nature of contemporary governments, politics and social orders. The national polities of the modern world maintain their existence by deliberately fostered craving and fear: monstrous protection rackets. The “free world” has become economically dependent on a fantastic system of stimulation of greed which cannot be fulfilled, sexual desire which cannot be satiated and hatred which has no outlet except against oneself, the persons one is supposed to love, or the revolutionary aspirations of pitiful, poverty-stricken marginal societies like Cuba or Vietnam. The conditions of the Cold War have turned all modern societies — Communist included — into vicious distorters of man’s true potential. They create populations of “preta” — hungry ghosts, with giant appetites and throats no bigger than needles. The soil, the forests and all animal life are being consumed by these cancerous collectivities; the air and water of the planet is being fouled by them.

There is nothing in human nature or the requirements of human social organization which intrinsically requires that a culture be contradictory, repressive and productive of violent and frustrated personalities. Recent findings in anthropology and psychology make this more and more evident. One can prove it for himself by taking a good look at his own nature through meditation. Once a person has this much faith and insight, he must be led to a deep concern with the need for radical social change through a variety of hopefully non-violent means.

The joyous and voluntary poverty of Buddhism becomes a positive force. The traditional harmlessness and refusal to take life in any form has nation-shaking implications. The practice of meditation, for which one needs only “the ground beneath one’s feet,” wipes out mountains of junk being pumped into the mind by the mass media and supermarket universities. The belief in a serene and generous fulfillment of natural loving desires destroys ideologies which blind, maim and repress — and points the way to a kind of community which would amaze “moralists” and transform armies of men who are fighters because they cannot be lovers.

Avatamsaka (Kegon) Buddhist philosophy sees the world as a vast interrelated network in which all objects and creatures are necessary and illuminated. From one standpoint, governments, wars, or all that we consider “evil” are uncompromisingly contained in this totalistic realm. The hawk, the swoop and the hare are one. From the “human” standpoint we cannot live in those terms unless all beings see with the same enlightened eye. The Bodhisattva lives by the sufferer’s standard, and he must be effective in aiding those who suffer.

The mercy of the West has been social revolution; the mercy of the East has been individual insight into the basic self/void. We need both. They are both contained in the traditional three aspects of the Dharma path: wisdom (prajna), meditation (dhyana), and morality (sila). Wisdom is intuitive knowledge of the mind of love and clarity that lies beneath one’s ego-driven anxieties and aggressions. Meditation is going into the mind to see this for yourself — over and over again, until it becomes the mind you live in. Morality is bringing it back out in the way you live, through personal example and responsible action, ultimately toward the true community (sangha) of “all beings.”

This last aspect means, for me, supporting any cultural and economic revolution that moves clearly toward a free, international, classless world. It means using such means as civil disobedience, outspoken criticism, protest, pacifism, voluntary poverty and even gentle violence if it comes to a matter of restraining some impetuous redneck. It means affirming the widest possible spectrum of non-harmful individual behavior — defending the right of individuals to smoke hemp, eat peyote, be polygynous, polyandrous or homosexual. Worlds of behavior and custom long banned by the Judaeo-Capitalist-Christian-Marxist West. It means respecting intelligence and learning, but not as greed or means to personal power. Working on one’s own responsibility, but willing to work with a group. “Forming the new society within the shell of the old” — the IWW slogan of fifty years ago.

The traditional cultures are in any case doomed, and rather than cling to their good aspects hopelessly it should be remembered that whatever is or ever was in any other culture can be reconstructed from the unconscious, through meditation. In fact, it is my own view that the coming revolution will close the circle and link us in many ways with the most creative aspects of our archaic past. If we are lucky we may eventually arrive at a totally integrated world culture with matrilineal descent, free-form marriage, natural-credit communist economy, less industry, far less population and lots more national parks.

GARY SNYDER

1961