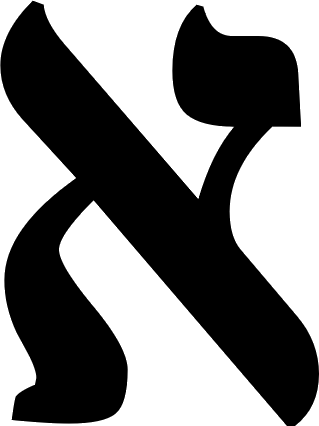

Note: This is the first day of Sukkot, the Jewish harvest festival that includes reading Ecclesiastes/Kohelet, one of my favorite books of the Hebrew Bible. Before writing a new post about Ecclesiastes, I reviewed my earlier posts that referenced it. It turns out the following was drafted but never published.

Kafka’s Parable (No answer to all questions, no solutions to all mysteries)

Kafka’s parable

Is a sounding of a bell

That half sickens me.

So obvious that

All searches do not succeed

Still hopeful that

Some do

Mine will.

Why embed the futility of Ecclesiastes

In a treasure map

That might as well say

Not here

Not here

Not anywhere.

Frustration is one thing

The waste of a life another.

© 2025 Bob Schwartz

Kafka’s parable, found in his novel The Trial, “can be read as a religious allegory or as an allegory of human justice.” (see below).

The futility found in Ecclesiastes (entitled in Hebrew Kohelet) refers to a repeated theme of the biblical book, starting with its famous opening passage. While there is much disagreement about the English translation of the biblical Hebrew word hevel—air, vapor, breath, mist, smoke, futility, meaningless, absurd, pointless or useless—the line “hevel hevelim, kol hevel” it is best known in English this way:

Futility, futility, all is futility.

From Tree of Souls:The Mythology of Judaism by Howard Schwartz

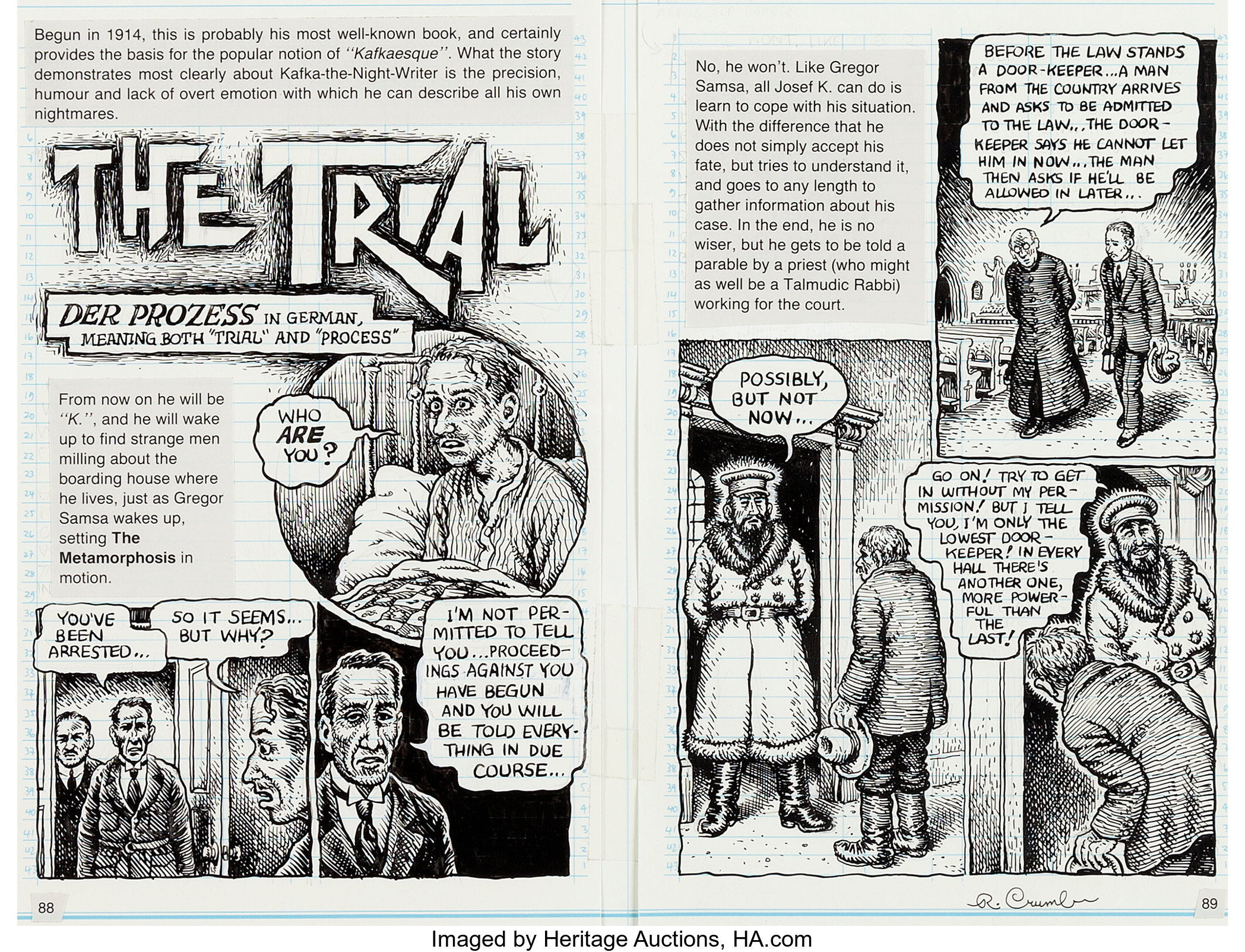

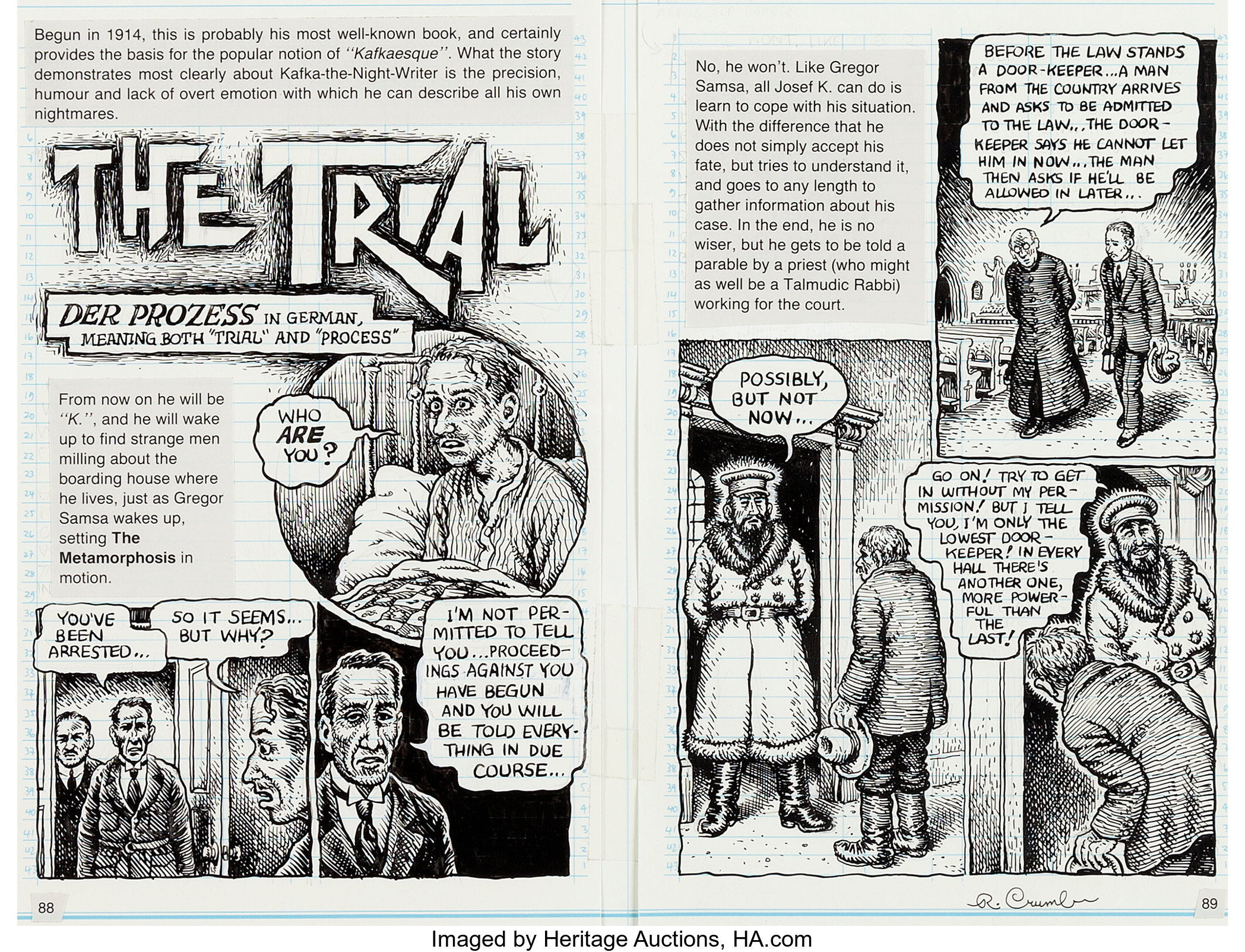

BEFORE THE LAW

Before the Law stands a man guarding the door. To this doorkeeper comes a man from the country who asks to be admitted to the Law. But the doorkeeper says that he cannot grant him entry. The man thinks about it and asks if, in that case, he will be permitted to enter later. “Possibly,” says the doorkeeper, “but not now.”

As the gateway to the Law is, as always, open, and the doorkeeper steps aside, the man stoops to look within. When the doorkeeper sees this, he laughs and says, “If it tempts you that much, just try to get in. But be aware that I am mighty. And I am only the lowliest doorkeeper. From hall to hall there are doorkeepers, each mightier than the one before. Even I can no longer bear the sight of the third of these.”

The man from the country has not expected such difficulties. Surely, he thinks, the Law ought to be accessible to everybody, always, but now as he looks more carefully at the doorkeeper, with his big pointed nose and long, thin, black Tatar beard, he decides he’d rather wait for permission to enter. The doorkeeper gives him a stool and has him sit down beside the door. There he sits for days and for years. He often tries to be admitted, and wearies the doorkeeper with his pleas. The doorkeeper frequently questions him, asks him about where he comes from and many other things, but they are distant inquiries, the sort great men make, and in the end he always says that he cannot let him in yet. The man, who has equipped himself for his journey with many things, employs everything, however valuable, to bribe the doorkeeper. He takes it all, saying however, “I accept this only so you won’t think you’ve failed to do anything.”

All these long years the man watches the doorkeeper unceasingly. He forgets the other doorkeepers, and this first one seems to be the only obstacle between him and the Law. He curses his miserable luck, at first recklessly and loudly; later, as he grows old, he only grumbles to himself. He becomes childish, and since his years of scrutiny of the doorkeeper have enabled him to recognize even the fleas in his fur collar, he asks even the fleas to help change the doorkeeper’s mind. Finally his eyes grow feeble, and he doesn’t know if it’s really getting darker around him or if his eyes are only tricking him. But in the darkness he now observes an inextinguishable radiance streaming out of the door of the Law.

Now he will not live much longer. Before he dies all he has been through converges in his mind into one question that he has never yet asked the doorkeeper. He signals to him, as he can no longer raise his stiffening body. The doorkeeper has to bend down low to him, as their difference in size has altered, much to the man’s disadvantage. “What do you want to know now?” asks the doorkeeper. “There’s no satisfying you.” “Everyone struggles to reach the Law,” says the man. “How can it be that in all these years no one but me has asked to get in?” The doorkeeper recognizes that the man’s life is almost over and, because his hearing is failing, he roars at him, “No one else could be allowed in here. This entrance was intended only for you. I am now going to close it.”

* * *

This famous parable by Kafka from The Trial can be read as a religious allegory or as an allegory of human justice. Although it is generally thought of more in terms of the latter, it has the distinct elements of a religious allegory. The key image is that “of an inextinguishable radiance streaming out of the door of the Law.” This clearly suggests the eternal nature of the Law, which, of course, draws this eternal quality from God. This shifts the focus of the parable from human justice to the need for divine justice, and hints at the remoteness of God.

The doorkeeper guarding the gate to the Law is reminiscent of the angel placed at the gate of the Garden of Eden, with the flaming sword that turned every way, to guard the way to the tree of life (Gen. 3:24). Also echoed is the popular Christian conception of St. Peter serving as the doorkeeper at the Gates of Heaven.

Gershom Scholem has said that there are three pillars of Jewish mystical thought: the Bible, the Zohar, and the writings of Kafka. Thus he viewed Kafka’s writings, which have been interpreted in a multitude of ways, as mystical texts. Scholem pointed out parallels between “Before the Law” and passages in the Hekhalot texts about angels guarding the gates of the palaces of heaven. For a description of these angels, see “The Entrance of the Sixth Heavenly Palace,” p. 178. Compare this description with Kafka’s description of the doorkeeper in “Before the Law.” The parallels are striking, but since this Hekhalot text was little known during Kafka’s lifetime, it is not likely that he had direct knowledge of it. Moshe Idel also identifies the quest in this tale as the remnant of a mystical one. See Kabbalah: New Perspectives, p. 271.

Another perspective is suggested by Zohar 1:7b: Open the gates of righteousness for me . . . . This is the gateway to the Lord (Ps. 68:19-20). Assuredly, without entering through that gate one will never gain access to the most high King. Imagine a king greatly exalted who screens himself from the common view behind gate upon gate, and at the end, one special gate, locked and barred. Said the king: “He who wishes to enter into my presence must first of all pass through that gate.”

Another parallel is found in Ibn Gabirol’s eleventh century treatise, The Book of the Selection of Pearls (ch. 8): “The following laconic observations are said to have been addressed to a king, by one who stood by the gate of the royal palace, but who failed to obtain access. First: Necessity and hope prompted me to approach your throne. Second: My dire distress admits of no delay. Third: My disappointment would gratify the malice of my enemies. Fourth: Your acquiescence would confer advantages, and even your refusal would relieve me from anxiety and suspense.”

Max Brod, Kafka’s close friend and biographer, comments about this parable: “Kafka’s deeply ironic legend ‘Before the Law’ is not the reminiscence or retelling of this ancient lore, as it would seem at first glance, but an original creation drawn deeply from his archaic soul. It is yet another proof of his profound roots in Judaism, whose potency and creative images rose to new activities in his unconscious.” (Johannes Reuchlin und sein Kampf, Stuttgart: 1965, pp. 274-275).

Of course, “Before the Law” can also be read as a personal statement of the kind of obstruction Kafka experienced at the hands of his father. The role of the gatekeeper can also be identified with Kafka’s mother, for Kafka gave his mother the epic letter he wrote to his father, to pass on to him, but she decided not to do so. In such a reading Kafka’s father represents the Law, the strict, godlike figure. See Kafka’s Letter to His Father.

Also, Kafka’s parable is relevant to human justice, where, on many occasions, people have been denied justice by the very ones who were supposed to provide it for them. In doing so they perform the obstructive role of the gatekeeper, who was supposed to welcome the man from the country at the gate intended only for him, but instead prevented him from entering at all.

Readers may wonder why a modern parable by Franz Kafka has been included in a book of Jewish mythology. There are several reasons for this. Kafka’s fiction possesses a strong mythic element, and scholars have become increasingly aware of the strong influence on it of Jewish tradition; Kafka’s writing in general, and this parable in particular, has taken on the qualities of a sacred text in our time; and there are strong parallels between this parable and traditional Jewish myths about the quest to reach God, but also a strong element of doubt in Kafka’s parable that reflects the modern era. Just as the evolution of Jewish mythology did not end with the canonization of the Bible or the Talmud, and continued to flourish in the kabbalistic and hasidic era, so too it can be seen to continue in the modern era in the writings of Kafka. It also can be found in other seminal Jewish authors, such as I. L. Peretz, S. Y. Agnon, Bruno Schulz, and I. B. Singer.