How special is the atomic bomb? So special that many nations want one, many nations have more than one, and yet despite how crazy and desperate some nations have been in the past decades, only one nation has ever used one. A hoarded treasure so dark that it is displayed and demonstrated but not deployed.

So special that it should be the zero of a standard human calendar. Just as Jews measure time from the creation of the world, Christians from the birth of Jesus, Muslims from the hijra from Mecca to Medina, we might all measure time from August 6, 1945.

The U.S. did drop atomic bombs. Twice in three days (August 6 on Hiroshima, August 9 on Nagasaki). And divided history in half, before and after. Before, things might be brutal, tens of millions might be slaughtered, but it would take superhuman effort, and would be followed by an opportunity, however arduous, to rebuild and repopulate. After, in these times, our times, there is a theoretical prospect of erasing some, most, or all of the world and its people. Not easily, but not that hard either, leaving behind a wasteland the size of a city or country or continent.

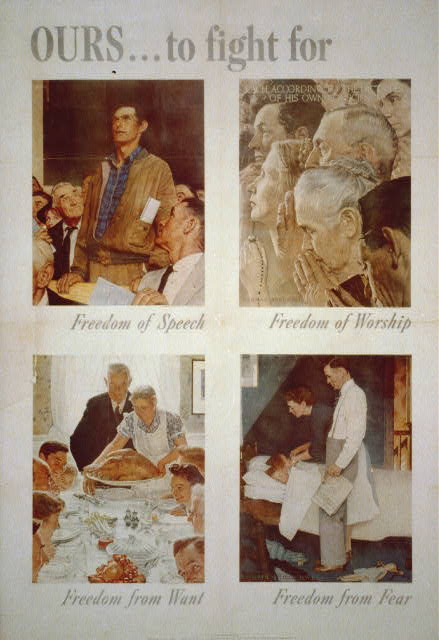

Above is a picture of the Hiroshima municipal flag, adopted by the city in 1896, almost fifty years before the weapon that destroyed and damaged so many lives. Historians still debate the effect and necessity of the Bomb in hastening the end of the war with Japan, an argument heightened when talking about the second bomb.

On this 70th anniversary, 70 After Hiroshima, let us focus on the flag.

Brief research doesn’t reveal much about the flag’s design. But students of Asian culture might see in it one of the eight I Ching trigrams, since the Chinese oracle has been widely used across Asian nations for thousands of years.

This particular trigram, composed of three unbroken lines, is Qian. When doubled it forms Hexagram 1 of the I Ching, also known as Qian. Heaven. The Creative. Sublime success.

John Minford explains in his recent translation:

Heaven above Heaven. Pure Yang. This is the first of eight Hexagrams formed by doubling a Trigram of the same Name. The word chosen for the Trigram/Hexagram Name, Qian, whatever its original meaning may have been (and there are many understandings of this), came in later times to be used more and more as a shorthand for Heaven, emblem of Yang Energy and Creativity.

The classic Wilhelm/Baynes translation notes:

The first hexagram is made up of six unbroken lines. These unbroken lines stand for the primal power, which is lightgiving, active, strong, and of the spirit. The hexagram is consistently strong in character, and since it is without weakness, its essence is power or energy. Its image is heaven. Its energy is represented as unrestricted by any fixed conditions in space and is therefore conceived of as motion. Time is regarded as the basis of this motion. Thus the hexagram includes also the power of time and the power of persisting in time, that is, duration.

The power represented by the hexagram is to be interpreted in a dual sense—in terms of its action on the universe and of its action on the world of men. In relation to the universe, the hexagram expresses the strong, creative action of the Deity. In relation to the human world, it denotes the creative action of the holy man or sage, of the ruler or leader of men, who through his power awakens and develops their higher nature.

THE JUDGMENT

THE CREATIVE works sublime success,

Furthering through perseverance.

We have come a long way in 70 years, and whether or not that trajectory is to everyone’s liking, here we are. That we have managed not to drop any more nuclear bombs or fire any nuclear missiles might be a miracle, or might just be a sign of self-interest in survival coming before everything else.

That we did drop those bombs was a high price to pay for learning just how much damage the “good guys” were capable of and might feel compelled to perpetrate when dire circumstances seemed to call for it. It’s a lesson in self-awareness that we are still learning, more or less studiously. It’s a lesson that the traditions try to help us with. The devil, for example, is not an arm’s length third party who bargains and cajoles. The devil is in us, and handling it is one of our missions. The I Ching is clear on the fluid dynamics of our lives and the world, knowing that we and it flow this way and that, and heaven can be hell for a while, maybe deep and for a long while, but not forever.