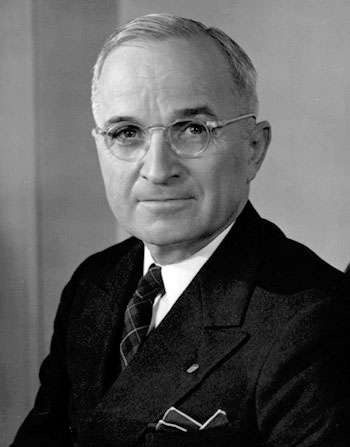

What Would Truman Do?

by Bob Schwartz

Harry Truman is maybe the most interesting American President of the twentieth century, and maybe the most significant.

He held a power that no one had held in human history and he took the decision to use it. He had no precedent to guide him—except maybe God in the Bible. He dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. From that point forward, everyone who uses nuclear weapons will be the second or third to do it.

He is also the only President in the twentieth century without a college degree, and one of the relatively few in American history. Grover Cleveland was the last before him. But there are some before that who did manage to stand out without college, such as George Washington and Abraham Lincoln.

Obama shares some things with Truman, and on other scores couldn’t be more unlike. Truman was an unabashed though pragmatic reformer: he used executive power to desegregate the military, but his Fair Deal liberal agenda failed in the face of a recalcitrant Republican Congress. Truman’s second term was the model for all other second term disasters, marked by a war that was both unpopular and unsuccessful and by a President whose effectiveness was a constant question.

Unlike Obama, Truman was not a spell-binding orator or a scholar. He had come up through politics and to the Senate the old back room way, and his ascension to the 1944 presidential ticket was a matter of political manipulation and happenstance. The legendary 1948 election pitted him against the dapper, smooth talking, hard-nosed, well-educated federal prosecutor and New York Governor. It was considered no contest for Thomas E. Dewey. Truman won.

The reasons that Truman has risen to the top ten on nearly all lists of great American Presidents (he is number 5 on a few) are many. This puts him in the range of both Roosevelts, TR and FDR, both of whom went to Harvard, both of them charismatic patricians with colorful histories and silver tongues. Among Truman’s gifts, the one most associated with him was a plain-spoken decisiveness in word and deed, even if the decision turned out troublesome or wrong.

There were reasons to like Truman at the time of his presidency, and a number of reasons not to. But there was a sense—even those who were his enemies at the time acknowledge it and historians have come to treasure it—that underneath it all was a man who had fought in a world war (only a few Presidents have), a man who had lived a modest life, a man who knew how to practice politics, a man who could surprise by analyzing deeply, a man who faced with the prospect of killing hundreds of thousands of people in a moment gave the order to do it.

Plain speaking. Decisive action. Truman was not the ideal President because there is no such thing. But at every critical juncture, it can’t hurt to ask: what would Truman do?