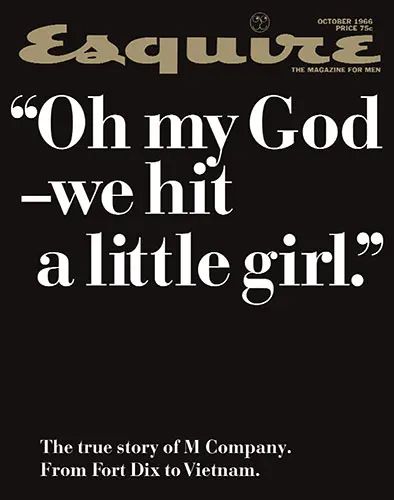

“Oh my God—we hit a little girl.” M Company, Vietnam, 1966. Oh my God—we hit a girl’s school in Iran, 2026.

The above Esquire magazine cover and story from October 1966 is famous, both as a work of stunning graphic art designed by George Lois and as an early harbinger of what a disaster the Vietnam War could and would become.

On February 28, 2026, a girl’s primary school in Tehran was decimated in a strike, leaving 168 dead. Trump said it was done by Iran, U.S. intelligence suggested that it might possibly be a U.S. strike, and a video now confirms that it was a U.S. Tomahawk missile. We did it.

You can judge whether this is an acceptable consequence of an incoherent war. It is not the first incoherent and deadly war the U.S. has chosen, though it may be the most incoherent.

For historical perspective, below is the Esquire story that goes with the cover.

M

M is M Company of the 1st Advanced Infantry Training Brigade in the United States Army Training Center, Infantry, at Ft. Dix, New Jersey, the training cycle of December 13, 1965, to February 3, 1966. It was assigned to the 1st Infantry Division at Di An and to A, B, and C Companies of the 2nd Battalion of the 2nd Infantry, in the 3rd Brigade of the 1st Infantry Division, at Lai Khe. Its first operation was Operation Mastiff, the week of February 21, 1966.

One, two, three at the most weeks and they would give M company its orders—they

being those dim Olympian entities who reputedly threw cards into an IBM machine or into a hat to determine where each soldier in M would go next, which ones to stay there in the United States, which to live softly in Europe, and which to fight and to die in Vietnam.

No matter. What agonized M this evening wasn’t what was in its cards but what was in the more immediate offing—an inspection! indeed, its very first inspection by its jazzy young Negro captain. So this evening M was in its white Army underwear waxing the floor of its barracks, shining its black combat boots, turning the barrels of its rifles inside out and picking the dust flecks off with tweezers, unscrewing its eardrums—the usual. The air was thick with the smell of floor wax and rifle oil, a moist aroma that now seemed to M to be woven into the very fabric of Army green. Minutes before, the company had heard a do-or-die exhortation by its bantamweight sergeant, Sergeant Milett. Get yourself clean for my sake, Milett had told M. “I’ve got a wife, three kids at home. I leave in the dark, I come home in the dark. I haven’t talked to them in thirty-six hours. I don’t know, maybe they’re dead,” using psychology, leaning against a two decker bed, reaching an arm through the iron bedstead, beseechingly. “Well …” making a joke of it, “I left them enough food, I shouldn’t have to worry,” and getting to the point, “I got a boss downstairs, he got a couple bars on his collar, he is the boss I work for. Tomorrow afternoon he will inspect us: don’t make a jackass out of me!”

And all you’ve got to do is follow the chart! and M company, now in its fourth quick month of Army life and last of infantry training at a large and bleak Eastern camp, had known what Milett meant. The chart appeared in the Soldier’s Handbook and it bore the enacting signature of the Army’s adjutant general, none other. The insides of a guy’s green footlocker (the general had commanded) should be like so; and what a proud inspection they’d have if M would just faithfully comply! The general had ordered that Pepsodent or whatever brand of tooth powder a boy enjoyed must go to the rear of the footlocker, left, it mustn’t be dirty or dusty, and it must be bottom backwards so the words TOOTH POWDER appeared upside-down, who would have thought it? The general had charged that a fellow’s SHAVING CREAM go to the right while his razor, his blade, his toothbrush, and his comb all covered down on his soap dish; and everything must lie on his whitest towel, the general had declared. To this Army-wide order of battle a mere master sergeant in M’s training camp had dared add an innovation: he allowed that a Bible might lie in that footlocker in between the handkerchiefs and the shoe polish, rightside-up. This would be optional, a matter of a man’s conscience; but other deviations from the archetypical footlocker, the wall locker, the steel combat stuff to be laid on a soldier’s bunk, or the soldier himself—would be gigged, Milett had reminded everyone, and gigged would mean no going home Saturday night; no passes.

“So … try. Follow the chart,” he had pleaded and hurried to where his wife and his children, whew, still lived, and M, a body of two hundred and fifty American boys of all shapes and sizes and wild idiosyncrasies, most of them draftees, some of them volunteers—M company was getting its house in order conscientiously, in some cases even willingly. But not in Private Demirgian’s. Demirgian thought it was idiotic, all this footlocker, wall locker, fleck-of-fluff-on-your-shoelace stuff—senseless, most of M would agree but Demirgian alone conspired with himself to get discharged; out, a consummation that he tried to effect by exercising his will-o’-the-wisp power. Demirgian built castles in Spain, in Armenia, in any area M wasn’t—he dared to have madly escapist flights of imagination because his intuition secretly assured him that they’d come to naught. He had said to himself once, I could walk in front of somebody’s rifle. He had thought he could fall downstairs and tell the doctors, “My brain—it’s loose, it’s rattling around inside my head,” he had come a cropper playing football once and that is how Demirgian’s brain had felt, he knew the symptoms. As yet, none of his schemes had become a clear and present danger to M’s staying at full strength—but Demirgian had a new thought tonight. His fancy had seized on something that a hard-eyed private had said in the course of a ten o’clock whiskey break, a private who’d been an assistant policeman, a meter maid or something, in Youngstown, Ohio, who had said, a blow in precisely the right part of a jaw would break it. Demirgian, his intellect stimulated and his inhibition paralyzed by two J&B’s, now replied, “Yaa!” or words to that effect.

“Twenty dollars!” the former policeman cried, whipping a wallet out of his vast Army fatigue pocket, slapping a bill of that denomination on the windowsill, clenching his other fist. “Twenty dollars says I can do it.”

“Yaa! There was a guy twice as big as you, he hit me right here and he couldn’t break it.”

“That’s not where I’m going to hit you, Demirgian! Where is your twenty?”

“I’ll owe it,” already conceding.

“Twenty dollars, Demirgian!” said Youngstown’s finest, slapping his green gauntlet down again. He had picked up the bill while nobody watched, apparently—he liked its brave sound on the concrete windowsill, smack! the sound of Demirgian’s jaw cracking like a chicken’s wishbone. He didn’t like Demirgian anyhow. Demirgian didn’t stand tall, as soldiers should. Demirgian slouched, he carried his head tilted like a damn violinist, and when he talked it rolled like a basketball on a rim, nature imitating Brando’s art.

“I’ll give you an IOU!”

“Shake! Raise up your chin,” and Demirgian did. “A little toward the window,” and Demirgian did—Demirgian in some dentist chair, his head tilted, jaw slack, eyes resting tensely on the orange NO SMOKING that was stenciled on M’s concrete wall. All of M’s sleeping quarters were interior decorated like any city apartment house in its cellar, where the washing machines are. The lengthy low building looked from the outside as though people inside might be working at lathes, and over the black door it announced to all humanity, “M” in black paint.

“Dammit—more to the right.”

“I’m waiting. I’m waiting,” Demirgian said while in some buried subconscious area he may have thought, my friends better rescue me—which seconds later they did.

“Easy! Yesterday at the 45 range he said to shoot him in the toes,” his buddy Sullivan said, stepping between them. “All he wants is get discharged.”

“Sure,” Demirgian agreed. He had been telling himself, well … either that or I’ll make twenty dollars, the Army hadn’t paid him in months, something was wrong at the finance office.

“You won’t get out of the Army with a broken jaw,” Sullivan talking.

“Sure—I won’t be able to eat. I’ll waste away.”

“Crazy. They’ll have you wired up in one day. You want to get out of the Army, get him to break your foot.”

“Can you break my foot?” Demirgian asked, but there is a tide in men’s affairs. Already the former policeman was telling his friends yes! he had been drinking whiskey but he wasn’t drunk, he would straight-line any of them—twenty bucks! but M was back getting ready for that inspection. All of this happened—do understand. Demirgian is real, so is everyone in this narrative, even the Chillicothe milkman: all about him shortly. Names and hometowns [appear at the end of the story], middle initials too, apologies to Ernie Pyle.

Anyhow. By two in the morning, all of M’s fingernails clean, its blankets as tight as a back plaster, its boots luminous, its combat equipment Brillo-bright and displayed on its bunks in harmony with the general’s chart, M company fell asleep in its sleeping bags on the only place left to it—the floor, as infinitesimal iotas of dust silently came to rest on its handiwork.

M was awakened at four o’clock. Today it devolved on the Chaplain to keep it from falling asleep again just after breakfast, for he would be giving M the day’s first class. Though his subject—”Courage”—wasn’t one notably rich in Benzedrine content, the Chaplain, a Protestant major, intended to say things like, “I suggest to you that it takes a man with courage of conviction to—” and here he would strike the flat of his palm against his wooden podium (his pulpit, he called it), jerking M out of its stupor in time to hear him finish his sentence, the text to this surprising gesture—”—to put your foot down.” He had many tricks, this Chaplain; sometimes he made noises but he had silences, too. He intended to say today, “Do you know what takes courage in a foxhole? It is this,” and then he would say ” … ,” he would say nothing, eons of empty time would go by while everyone’s eyes popped open to see if the bottom had dropped out of the universe; and then the Chaplain would say, “It isn’t the noises that get you, it’s the silence.” Also the Chaplain would have movies.

M got to his great concrete classroom at eight o’clock on this piercingly cold winter morning. In the vast reaches above it, sparrows sat on the heating pipes and made their little squeaking sounds. A sergeant shouted, “Seats!” and as M sat down on the cold metal chairs it shouted back in unison, “Blue balls!” or so one thought until one learned that M had shouted “Blue bolts!” the nickname of its brigade. M was a shouting company. It built up morale, its high-stepping Negro captain believed; also it kept M awake. Breakfast, lunch, and supper at M were a real bedlam because as each soldier entered the busy mess hall he had to left face and stand at attention, and bellow at a sergeant the initials signifying whether he had been drafted or had joined the Army voluntarily. “US, Sergeant!” “RA, Sergeant!” After the meals, the sergeants totaled up each category before reporting it to the mess sergeant, who filed it one whole month before throwing it away.

“Good morning, men,” said the Chaplain. He wore his wool winter field clothes with his black scarf, the symbol of the chaplains corps.

“Good morning, sir! Blue bolts! On guard! Mighty mighty Mike! Aargh!” M shouted back. The expression Blue bolts—we’ve been through that. The brigade’s motto was On guard, and Mike is phonetic alphabet for M; and Mighty it perfunctorily called itself. Aargh was needed for reasons of rhythm, like coming back to the tonic at the close of a song.

Both hands on his pulpit, the Chaplain now pushed it forward a few inches across the black linoleum. Scree-e-ch! and everyone in M sat blue-bolt upright as the Chaplain began speaking. He said, “Courage. … “

But at this instant a very important event was happening one hundred miles away. And if M had only known what a fragile vessel all of its hopes reposed in that morning, its thoughts would have leapt from the Chaplain’s lecture and fled across the intervening states to settle upon (a fanfare, please) … the Chillicothe milkman! His name was Elmer Pulver. His was the route east of the N&W tracks in Chillicothe, Ohio, in 1950, when the Korean war began. Elmer in his creaky horse-drawn cart, bringing in newspapers from the gate, rapping on the door cheerily, tat-a-tat-tat, closing the gate behind him so the dog couldn’t get out, the nicest, most up-and-coming milkman in town, giving little tasty chips of ice to the same Chillicothe children who would be draft eligible when he was a major in the U.S. Army in Washington, in 1966. Pulver was called up in 1951, but he chose to be an officer instead. Having asked for the infantry first, tanks second, artillery third, he was granted none of these, and as a young lieutenant of engineers, having asked for Korea, he was flown away to Germany—ah, the whimsical they! By 1966, Pulver, now a major and still terribly nice, had been given a desk in the Pentagon’s windowless inner rings, also an old wooden swivel chair and a new task: every (would you believe it? every) man in the Army, after he was through training would be assigned to a duty station by Major Pulver. Far from being three horrid witches on a heath somewhere dancing around a pot, they would be Elmer Pulver.

This winter morning he had a stack of those stiff IBM cards the size of an old British pound note, one apiece for every soldier in M. These cards had green edges, and Pulver had a second deck of colorless IBM cards, one apiece for everywhere on earth that the Army had an opening for riflemen. Seated at his swivel chair, Pulver now took a corncob from its round rack, filled it with tobacco, lit it, and started fingering through his IBM’s. Doing it the Army way, he would need to take absolutely any green card and white card and fasten them together with a paper clip: rifleman and assignment and on to the next, another day, another dollar. But the Major was a nice person; he knew he had human beings of many kidneys there in his busy fingers and though it meant working overtime—today was a Saturday, the Pentagon was strange and empty—he wanted to put each soldier where he’d be happiest. And on each boy’s IBM card there was a code letter signifying where on this varied planet he would truthfully hope to be stationed next.

Some of M wanted the dolce vita in Europe. Some had opted for sunny Hawaii or the Caribbean’s warm waters. A few adventurous souls had elected Japan. Were the IBM cards to be believed, none of M’s two hundred and fifty soldiers wanted to go to Vietnam—but this wasn’t so, the cards weren’t right. Bigalow wanted to go to Vietnam. He wanted this for that stock American reason, making money—for in Vietnam’s jungles he would earn $65 a month combat pay, which he figured would add to $780 after his twelve months’ tour of duty. This he figured to put into IBM: where, he figured, in a few thrifty years it would appreciate to $1,000, which—but beyond that Bigalow hadn’t figured. But thus far in his Army career, Bigalow hadn’t made his preference known to the proper authorities, no fault of his. Many nights earlier, a tall PFC from personnel office had gathered M together in its dayroom—a rumpus room, an area whose bright green pool and ping-pong tables a soldier saw whenever he was on detail to shine the linoleum beneath them; otherwise it was kept behind a steel chain, off limits. That night, though, it had been opened extraordinarily to let that PFC give everyone some little grey mimeographed forms. “Awright!” he had said. “Now! Those who would like to go to Europe write down Europe,” no promises made. He himself had taken one mimeographed form and curled it around his index finger, and while he spoke he wiggled it like a swizzlestick in a highball glass or a pencil making O’s: a gesture by which he might mean the Army’s having its people eternally fill in mimeographed forms. In fact, M had filled in forms so habitually that within minutes it would forget forever ever having completed this. “Awright,” said PFC Swizzlestick. “Those who want the Caribbean … ” and similarly for Alaska, Hawaii, Japan, Korea, Okinawa, and Bigalow’s coveted Vietnam. Then he had gathered up the mimeographed papers and cabled them to the Pentagon, but Bigalow was on KP that evening, standing in white clouds of steam and washing pans. So the code letter on his green IBM card was an X, meaning no known preference.

Puffing his corncob and thumbing through his second deck of cards, Pulver now learned that in one month the Army had vacancies in Germany and in Vietnam—no place else. Now it happened this freezing Saturday that he had brought his blond and eightyear- old son, Douglas, to the Pentagon (in a week it was Lisa’s turn) and to satisfy Douglas’ curiosity he showed him the IBM cards, explaining that a soldier who wanted to go to Europe would and that a soldier would go to Vietnam who wanted it—though none did. “Supposing he wants to go to Japan?” Douglas alertly asked, and Pulver explained that though there were no openings that month in this pretty land of geisha girls and cherry blossoms, though there were no Japanese slots he would do his level best by that soldier and order him to Vietnam, since he seemed interested in the Orient and could stop in Japan itself, perhaps, going over or coming back. “Supposing he wants Hawaii?” Douglas said, and Pulver replied: the same, he would go to Vietnam. “Daddy! I can do it myself—please,” Douglas said, but Daddy chuckled and said no, and as Douglas sat across from him with a set of crayons drawing some colorful jet airplanes his father began to clip cards together, the green and the white. At noon Douglas ate a hamburger at his desk, Pulver had a roast-beef sandwich on white bread at his.

At noon an apprehensive M waited in its tidy barracks for Captain Amaker’s arrival. Amaker, though, was innocently upon the turnpike in his white Triumph convertible gaily driving to New York City. Ha ha! it had been a trick, really the Captain had never been under the walnut shell. Sly old Milett, that cunning sergeant, had simply made M scrub itself harder by invoking Amaker’s awesome name—Amaker who really intended to be in Harlem that afternoon digging the jams there with a friend who pulled down $50 an hour sitting in chairs with an Olivetti and looking over his shoulder as though to say, “As long as you’re up, get me a Grant’s,” in the studios of Ebony magazine’s photographers. Instead, M would have its adequacy appraised by that fox in sheep’s clothing, Sergeant Machiavelli—Milett. He started inspecting the barracks at two o’clock. He wasn’t in any very aggravated mood until a moment later, when his fingers moved across the very first soldier’s footlocker in order to open it. And then Milett recognized from the almost imperceptible impedance that it gave to his fingertips the presence of that loathsome substance to whose annihilation he had devoted much of his Army career. He cried out “Dust!” and stretching his fingers wide enough to hold a basketball he pushed them at the face of the footlocker’s unfortunate owner, whose name was Private Scott. “Goddam! This is a shame,” Milett cried, and Scotty looked truly contrite, eyes on the floor. Usually he was a fun-loving guy, a Negro. The day before Swizzlestick’s poll he had watched Hawaiian Eye, and on the mimeographed questionnaire he had written, “Hawaii,” so that he could dance with the lulu girls.

“Dust! … Dust! … Dust! … All of them!” Milett said, hurling himself from locker to locker and giving each the fingertip test, a furious Pancho Gonzales forehand. “This is a court-martial offense! You aren’t ready for inspection!” he screamed—and suddenly his face wasn’t purple, his skin wasn’t bedsheet tight, the Sergeant was no longer angry. He laughed. He had realized, this whole thing was ridiculous—ridiculous, that a man should present himself for inspection with his footlocker dusty. “You people … you people,” laughing, taking his handkerchief out, wiping the filth from his fingers. “You better wake up, you people don’t wake up now you’ll never wake up. Only with a bad-conduct discharge. And,” his head shaking incredulously, “this is just a sergeant’s inspection, suppose it had been the Captain himself!” Cap-tain-him-self is how he pronounced it; quick little quarter-notes. Milett was a Puerto Rican. Three times the Caribbean had knocked down the house where he’d grown up; immigrating to Harlem, shining people’s shoes so he could take his girl to the movie but worrying what if she should see me shining shoes, washing his hands with Borax but thinking if I touched her maybe she’d smell it—ten years, and then he had found the Army, where a life to be proud of lay within a man’s aspirations: even a Puerto Rican’s. He said to M now, “I was a PFC,” pronouncing it pee-eff-see. “When the officer opened my locker he had to use sunglasses! because I didn’t have a towel there, I had aluminum foil all around! And he said to me,

You’re going to make it some day.” Milett’s eyes shone as he remembered, there was silverfoil behind his irises. What he couldn’t reconcile himself to and couldn’t forgive was that M didn’t have initiative—M didn’t really care.]

His punishment: no passes that Saturday afternoon. With those melancholy words Milett went to his rooms on the Army post, where he told the day’s happenings to his shapely, sweater-wearing wife, showing her the tainted handkerchief. Demirgian and most people went to sleep on their brown Army blankets. Pulver finished his work, and after driving Douglas home he took the family’s beagle, Socks, to the veterinarian’s, who gave it shots against hepatitis, distemper, and other diseases of dogs.

“I hate to see-e-e, de ev’-nin’ sun go down. … ” At the enlisted men’s club, a baldheaded man picked concernedly on his banjo, bending over it as though to loosen a knot in one string. He seemed to be thinking … almost … almost. On center stage in their spangled dresses the Barnes sisters did their little dance, and Prochaska, one of M’s few emissaries on the club’s folding seats, sang quietly along, tapping his visored hat against one knee. “Oh, I hate to see-e-e. … ” At seven that evening Milett had given M its passes—but Prochaska couldn’t leave, he didn’t have the money, they hadn’t paid him in months. Something was wrong at the finance office.

John Sack

Esquire, October 1966