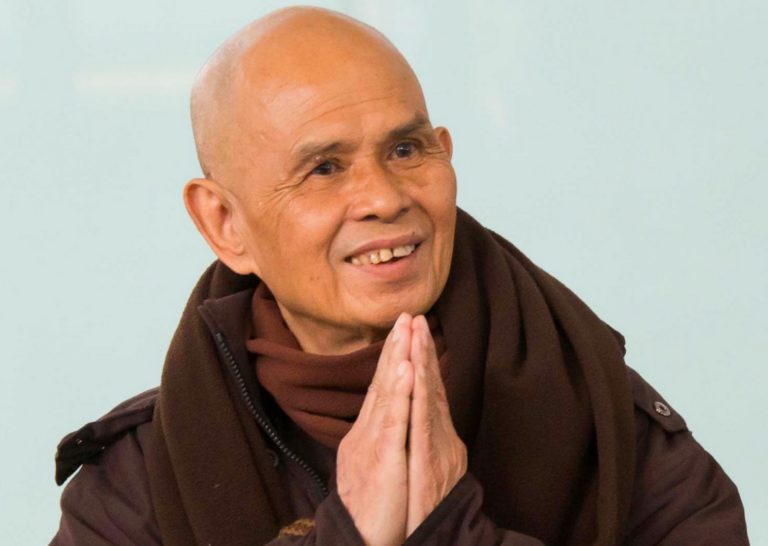

Nine Prayers by Thich Nath Hanh

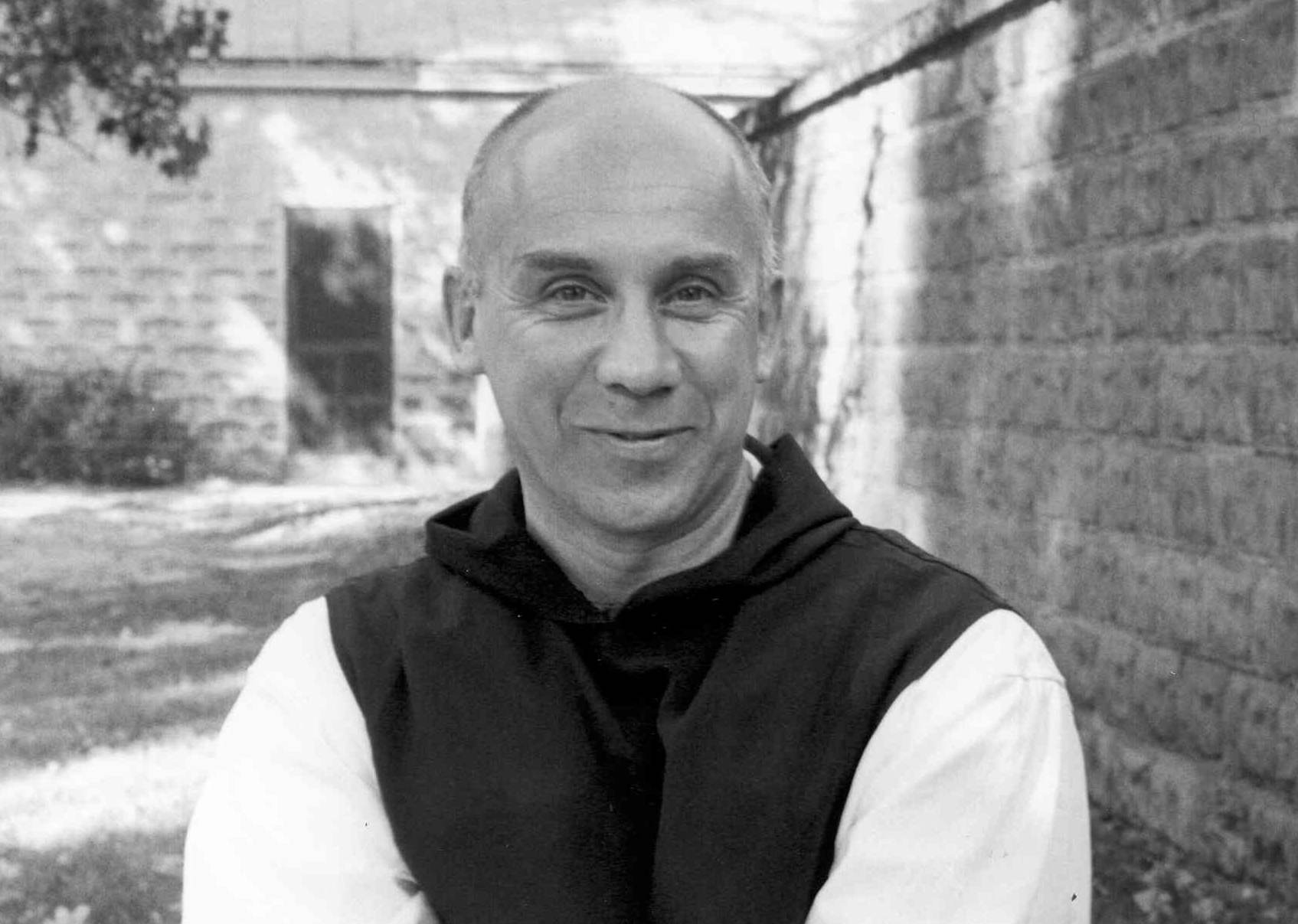

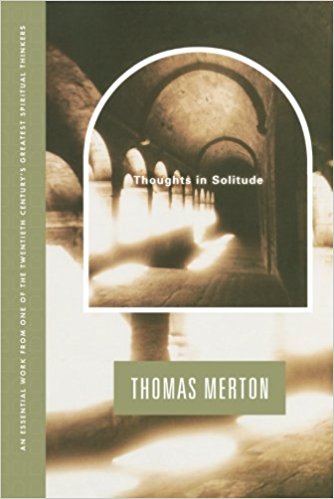

Thomas Merton’s final book, Contemplative Prayer, was published in 1969, a year after his accidental death. In 1995, Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh added an introduction. He wrote about his admiration for Merton and about distinctions between Christian and Buddhist prayer:

“I first met Thomas Merton in 1966. It is hard to describe his face in words, to write down exactly what he was like. He was filled with human warmth. Conversation with him was so easy. When we talked, I told him a few things, and he immediately understood the things I didn’t tell him as well. He was open to everything, constantly asking questions and listening deeply. I told him about my life as a Buddhist novice in Vietnam, and he wanted to know more and more.

Our approach to prayer in Buddhism is a little different from that of Christianity. We practice silent meditation, and we try to practice mindfulness in everything we do, to awaken to what is going on inside us and all around us in each moment. The Buddha taught: “If you are standing on one shore and want to cross over to the other shore, you have to use a boat or swim across. You cannot just pray, ‘Oh, other shore, please come over here for me to step across!’” To a Buddhist, praying without also practicing is not real prayer.”

At the end of his Introduction, Thich Nhat Hanh offers a set of nine prayers—prayers beyond any sectarian tradition.

Nine Prayers

Thich Nhat Hanh

From Contemplative Prayer by Thomas Merton

1.

May I be peaceful, happy, and light in body and spirit.

May he/she be peaceful, happy, and light in body and spirit.

May they be peaceful, happy, and light in body and spirit.

2.

May I be free from injury. May I live in safety.

May he/she be free from injury. May he/she live in safety.

May they be free from injury. May they live in safety.

3.

May I be free from disturbance, fear, anxiety, and worry.

May he/she be free from disturbance, fear, anxiety, and worry.

May they be free from disturbance, fear, anxiety, and worry.

4.

May I learn to look at myself with the eyes of understanding and love.

May he/she learn to look at him/herself with the eyes of understanding and love.

May they learn to look at themselves with the eyes of understanding and love.

5.

May I be able to recognize and touch the seeds of joy and happiness in myself.

May he/she be able to recognize and touch the seeds of joy and happiness in him/herself.

May they be able to recognize and touch the seeds of joy and happiness in themselves.

6.

May I learn to identify and see the sources of anger, craving, and delusion in myself.

May he/she learn to identify and see the sources of anger, craving, and delusion in him/herself.

May they learn to identify and see the sources of anger, craving, and delusion in themselves.

7.

May I know how to nourish the seeds of joy in myself every day.

May he/she know how to nourish the seeds of joy in him/herself every day.

May they know how to nourish the seeds of joy in themselves every day.

8.

May I be able to live fresh, solid, and free.

May he/she be able to live fresh, solid, and free.

May they be able to live fresh, solid, and free.

9.

May I be free from attachment and aversion, but not be indifferent.

May he/she be free from attachment and aversion, but not be indifferent.

May they be free from attachment and aversion, but not be indifferent.

He/she: First the person we like, then the person we love, then the person who is neutral to us, and finally the person we suffer when we think of.

They: The group, the people, the nation, or the species we like, then the one we love, then the one that is neutral to us, and finally the one we suffer when we think of.