Happy Bright Friday

Please pull back for a moment from thinking about what bargains we might find on Black Friday.

Black Friday used to be the one day after Thanksgiving, but is now an entire season of deals that seems to begin in October.

If you step back from bargain hunting, you might wonder why it is called “Black Friday”.

The term “Black Friday” has an interesting history. While widespread retail sales on this day began in the mid-20th century, the name itself has contested origins:

The most commonly cited explanation is that it refers to retailers moving from being “in the red” (operating at a loss) to being “in the black” (turning a profit) due to the surge in sales. However, this explanation appears to be a later rebranding.

The term actually originated in Philadelphia in the 1960s, where police used it to describe the chaos of heavy pedestrian and vehicle traffic that flooded the city the day after Thanksgiving. The crowds came for the Army-Navy football game held on Saturday and began their holiday shopping on Friday. Police had to work long shifts dealing with traffic and crowds, which they found unpleasant—hence the “black” descriptor.

Retailers initially disliked the negative connotation and tried to rebrand it as “Big Friday,” but the name Black Friday stuck. By the 1980s, retailers embraced the term, reframing it with the more positive “red to black” accounting narrative.

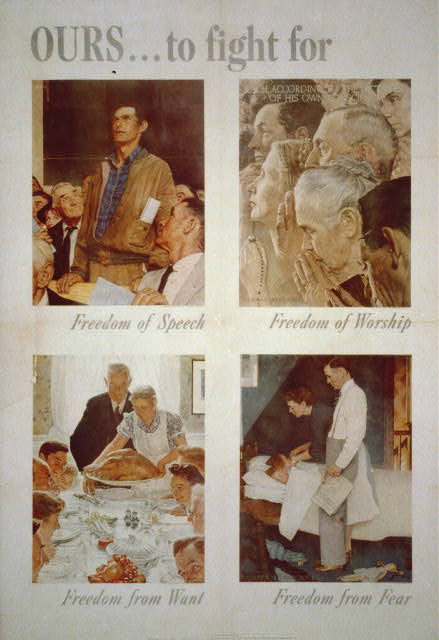

Just for a moment—the deals will wait—let’s change colors. Yesterday, at Thanksgiving, we may have been able to share company and a table with family and friends. In the coming weeks, we will be celebrating holidays that have light as a theme.

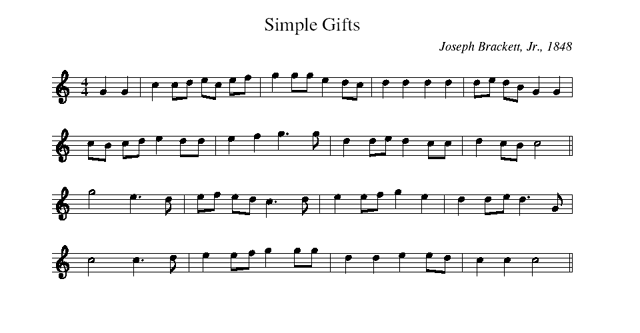

So let’s set aside the black and feature the light. This, the day after Thanksgiving, is Bright Friday. Are there light Bright Friday things waiting to be grabbed? Sure, if you know what they are and can find them.

Happy Bright Friday!

© 2025 Bob Schwartz