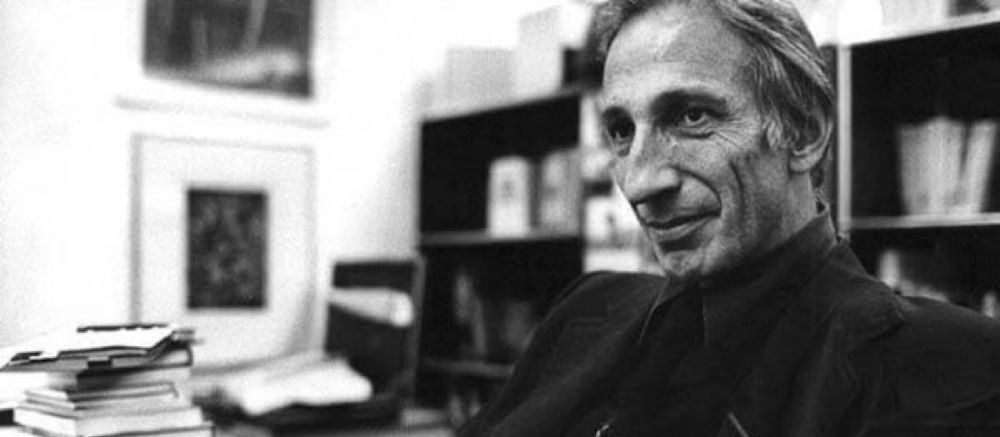

Prophetic perspective on AI: Ivan Illich and Tools for Conviviality

“One of the world’s great thinkers…. in the last 20 years of his life he became an officially forgotten, troublesome figure. This position obscures the true importance of his contribution.”

Guardian obituary of Ivan Illich, 8 December 2002

“The hypothesis on which the experiment was built must now be discarded. The hypothesis was that machines can replace slaves. The evidence shows that, used for this purpose, machines enslave men.”

Ivan Illich, Tools for Conviviality (1973)

If you have heard of Ivan Illich or include him in your conversations, you are in a small minority. His published critiques of major institutions—education, medicine, technology—had the establishment and those increasingly dominant institutions treating him as a “troublesome” marginal thinker. When you read Illich today, however, he comes across like a prophet. Prophets are almost always troublemakers.

From the Guardian obituary:

Ivan Illich: A polymath and polemicist, his greatest contribution was as an archaeologist of ideas, rather than an ideologue

Andrew Todd and Franco La Cecla

Sun 8 Dec 2002

Ivan Illich, who has died of cancer aged 76, was one of the world’s great thinkers, a polymath whose output covered vast terrains. He worked in 10 languages; he was a jet-age ascetic with few possessions; he explored Asia and South America on foot; and his obligations to his many collaborators led to a constant criss-crossing of the globe in the last two decades.

Best known for his polemical writings against western institutions from the 1970s, which were easily caricatured by the right and were, equally, disdained by the left for their attacks on the welfare state, in the last 20 years of his life he became an officially forgotten, troublesome figure. This position obscures the true importance of his contribution….

Illich was born in Vienna into a family with Jewish, Dalmatian and Catholic roots. His was an errant life, and he never found a home again after his family had to leave Vienna in 1941. He was educated in that city and then in Florence before reading histology and crystallography at Florence University.

He decided to enter the priesthood and studied theology and philosophy at the Vatican’s Gregorian University from 1943 to 1946. He started work as a priest in an Irish and Puerto Rican parish in New York, popularizing the church through close contact with the Latino community and respect for their traditions. He applied these same methods on a larger scale when, in 1956, he was appointed vice-rector of the Catholic University of Puerto Rico, and later, in 1961, as founder of the Centro Intercultural de Documentación (CIDOC) at Cuernavaca in Mexico, a broad-based research center which offered courses and briefings for missionaries arriving from North America….

Illich retained a lifelong base in Cuernavaca, but travelled constantly from this point on. His intellectual activity in the 1970s and 1980s focused on major institutions of the industrialized world. In seven concise, non-academic books he addressed education (Deschooling Society, 1971), technological development (Tools For Conviviality, 1973), energy, transport and economic development (Energy And Equity, 1974), medicine (Medical Nemesis, 1976) and work (The Right To Useful Unemployment And Its Professional Enemies, 1978, and Shadow Work, 1981). He analyzed the corruption of institutions which, he said, ended up by performing the opposite of their original purpose….

Illich lived frugally, but opened his doors to collaborators and drop-ins with great generosity, running a practically non-stop educational process which was always celebratory, open-ended and egalitarian at his final bases in Bremen, Cuernavaca and Pennsylvania.

Ivan Illich, thinker, born September 4 1926; died December 2 2002

I have been rereading Tools for Conviviality, especially in light of the overwhelming AI phenomenon, and find it as insightful as anything I’ve read—even though it was written more than fifty years ago and it doesn’t directly address AI. Great thinking from great thinkers always ages well.

No brief excerpt can do Tools for Conviviality justice. Here are just a few paragraphs:

The symptoms of accelerated crisis are widely recognized. Multiple attempts have been made to explain them. I believe that this crisis is rooted in a major twofold experiment which has failed, and I claim that the resolution of the crisis begins with a recognition of the failure. For a hundred years we have tried to make machines work for men and to school men for life in their service. Now it turns out that machines do not “work” and that people cannot be schooled for a life at the service of machines. The hypothesis on which the experiment was built must now be discarded. The hypothesis was that machines can replace slaves. The evidence shows that, used for this purpose, machines enslave men. Neither a dictatorial proletariat nor a leisure mass can escape the dominion of constantly expanding industrial tools.

The crisis can be solved only if we learn to invert the present deep structure of tools; if we give people tools that guarantee their right to work with high, independent efficiency, thus simultaneously eliminating the need for either slaves or masters and enhancing each person’s range of freedom. People need new tools to work with rather than tools that “work” for them. They need technology to make the most of the energy and imagination each has, rather than more well-programmed energy slaves….

I here submit the concept of a multidimensional balance of human life which can serve as a framework for evaluating man’s relation to his tools. In each of several dimensions of this balance it is possible to identify a natural scale. When an enterprise grows beyond a certain point on this scale, it first frustrates the end for which it was originally designed, and then rapidly becomes a threat to society itself. These scales must be identified and the parameters of human endeavors within which human life remains viable must be explored.

Society can be destroyed when further growth of mass production renders the milieu hostile, when it extinguishes the free use of the natural abilities of society’s members, when it isolates people from each other and locks them into a man-made shell, when it undermines the texture of community by promoting extreme social polarization and splintering specialization, or when cancerous acceleration enforces social change at a rate that rules out legal, cultural, and political precedents as formal guidelines to present behavior. Corporate endeavors which thus threaten society cannot be tolerated. At this point it becomes irrelevant whether an enterprise is nominally owned by individuals, corporations, or the state, because no form of management can make such fundamental destruction serve a social purpose….

It is now difficult to imagine a modern society in which industrial growth is balanced and kept in check by several complementary, distinct, and equally scientific modes of production. Our vision of the possible and the feasible is so restricted by industrial expectations that any alternative to more mass production sounds like a return to past oppression or like a Utopian design for noble savages. In fact, however, the vision of new possibilities requires only the recognition that scientific discoveries can be used in at least two opposite ways. The first leads to specialization of functions, institutionalization of values and centralization of power and turns people into the accessories of bureaucracies or machines. The second enlarges the range of each person’s competence, control, and initiative, limited only by other individuals’ claims to an equal range of power and freedom.

To formulate a theory about a future society both very modern and not dominated by industry, it will be necessary to recognize natural scales and limits. We must come to admit that only within limits can machines take the place of slaves; beyond these limits they lead to a new kind of serfdom. Only within limits can education fit people into a man-made environment: beyond these limits lies the universal schoolhouse, hospital ward, or prison. Only within limits ought politics to be concerned with the distribution of maximum industrial outputs, rather than with equal inputs of either energy or information. Once these limits are recognized, it becomes possible to articulate the triadic relationship between persons, tools, and a new collectivity. Such a society, in which modern technologies serve politically interrelated individuals rather than managers, I will call “convivial.”

After many doubts, and against the advice of friends whom I respect, I have chosen “convivial” as a technical term to designate a modern society of responsibly limited tools…. I am aware that in English “convivial” now seeks the company of tipsy jollyness, which is distinct from that indicated by the OED and opposite to the austere meaning of modern “eutrapelia,” which I intend. By applying the term “convivial” to tools rather than to people, I hope to forestall confusion.

“Austerity,” which says something about people, has also been degraded and has acquired a bitter taste, while for Aristotle or Aquinas it marked the foundation of friendship. In the Summa Theologica, II, II, in the 186th question, article 5, Thomas deals with disciplined and creative playfulness. In his third response he defines “austerity” as a virtue which does not exclude all enjoyments, but only those which are distracting from or destructive of personal relatedness. For Thomas “austerity” is a complementary part of a more embracing virtue, which he calls friendship or joyfulness. It is the fruit of an apprehension that things or tools could destroy rather than enhance eutrapelia (or graceful playfulness) in personal relations.

Ivan Illich, Tools for Conviviality