The Day the Buddha Woke Up

December 8 is Bodhi Day, the day on which the Buddha’s enlightenment is traditionally celebrated.

The English word “enlightenment” is so packed with meaning that it might be better to just go back to what the Buddha is reported to have said: I am awake.

This is useful because it leads to the two questions: woke up from what and woke up to what?

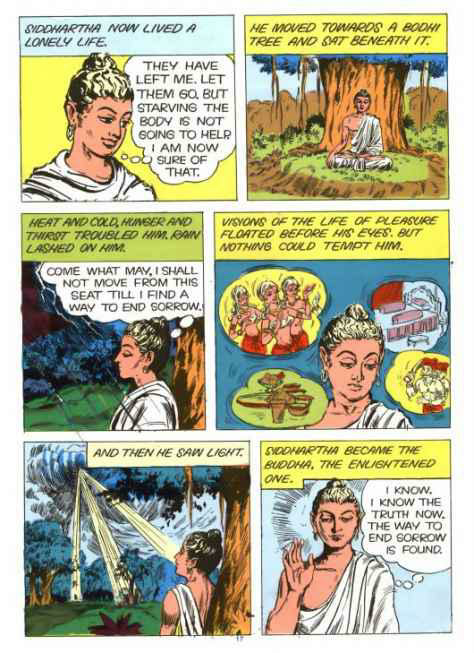

The Buddha, sitting there under the Bodhi tree, woke up from a journey. Born a royal son, he had fled a life of accidental privilege to answer ultimate questions about suffering and death—the very same questions that consume religious lives of all kinds. He believed that if he tried a, b, and c (such as extreme asceticism), he would discover some secret x, y, and z. There was some kind of magic formula, and all he had to do was learn it. That sort of magic is still at the heart of much of our religion.

He woke up to discover that there was no magic, not in such an instrumental sense. Nothing was different. Suffering and death would not go away, no matter what efforts we make. The best and worst aspects of life would go on, with and without us. Great fortunes would be made and lost. Great structures would be built and then destroyed, by cataclysms natural and human. Love would be here and gone.

But this: He could see something in all of that that made sense of all of that. There is no big plan in which we are players, active or passive, though we could and do make and execute our own little plans. There are just things, relationships between those things, and change, and of all those of a singular piece. We can and do overlay that with all of our very complicated details and distinctions, which is after all a definition of the life we live. But if we discover that underlying existence, we just might choose to live differently. And in that living differently, make change and wake others up. And on and on.

None of that eliminated suffering and death for the Buddha, as it won’t for anyone. He grew old and tired and, legend has it, died from being given spoiled food. He had told his followers what he had discovered, none of which involved magic. It was all about the infinite depth of the ordinary. For him, there was no more a kingdom in the clouds than the kingdom he had left behind when he started his journey. There was just what is. Strive on with diligence, he told those followers at the last.

© 2025 Bob Schwartz