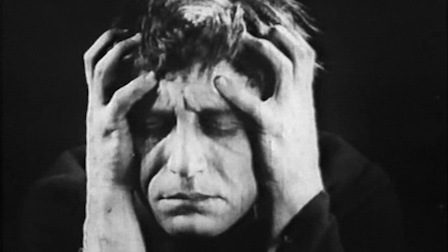

Crime and Punishment

It is just like a movie, some are saying.

No, like a novel.

Two brothers. The older one dead, run over by the younger. The younger on the run—maybe caught or even dead by the time this is read.

In the media, fragments of information are spun into explanations, like Rumplestiltskin’s straw into gold. It is the job of experts to provide answers, and when pieces are missing, to speculate. Can they be blamed?

Writers are the real experts at helping us on this. In 1962, when Truman Capote applied his considerable skill as storyteller to a pair of real-life cold-blooded killers, the book In Cold Blood became something new: the non-fiction novel. Critics celebrated, but others complained that the humanizing of evil made the author an accomplice.

A century earlier, Fyodor Dostoyevsky took an even deeper look at the mind of the killer, a fictional one, in Crime and Punishment. He did not minimize the horror of the crime or humanize the killer for purposes of sympathy, empathy or excuse. He instead set the standard for psychological depth and ambiguity that is the hallmark of modern literature since.

Standard or simplistic explanations and labels fit many needs, including the need of broadcasters to fill dead air while an extended manhunt and its aftermath proceed. But Dostoevsky demanded a trip on the subtle dark seas of family, society and the mind. That’s not just a way we understand the bad actors. It’s how we understand ourselves, even when our own seas are not nearly so dark.

From Crime and Punishment, as Rodion Raskolnikoff pursues his plan to kill the moneylender Alena Ivanovna. He walks down the street, when someone remarks about his unusual hat:

“I knew it,” he muttered in confusion, “I thought so! That’s the worst of all! Why, a stupid thing like this, the most trivial detail might spoil the whole plan. Yes, my hat is too noticeable…. It looks absurd and that makes it noticeable….With my rags I ought to wear a cap, any sort of old pancake, but not this grotesque thing. Nobody wears such a hat, it would be noticed a mile off, it would be remembered…. What matters is that people would remember it, and that would

give them a clue. For this business one should be as little conspicuous as possible….Trifles, trifles are what matter! Why, it’s just such trifles that always ruin everything….”

He had not far to go; he knew indeed how many steps it was from the gate of his lodging house: exactly seven hundred and thirty. He had counted them once when he had been lost in dreams. At the time he had put no faith in those dreams and was only tantalizing himself by their hideous but daring recklessness. Now, a month later, he had begun to look upon them differently, and, in spite of the monologues in which he jeered at his own impotence and indecision, he had involuntarily come to regard this “hideous” dream as an exploit to be attempted, although he still did not realize this himself. He was positively going now for a “rehearsal” of his project, and at every step his excitement grew more and more violent.