Cushion

Cushion

I look at the cushion

The cushion looks back

It has no clock

But I do

Come it says

Early I say

Come it says

And I do

Cushion

I look at the cushion

The cushion looks back

It has no clock

But I do

Come it says

Early I say

Come it says

And I do

Republicans in Congress seem to have lost their way. They could use a more altruistic, less self-serving vision of Americans and their lives.

Many of those members identify as religiously faithful, the majority faithful Christians.

What if some famous religious figures visit Congress and talk about its role in helping to make American lives better?

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington was made by legendary director Frank Capra, himself a faithful Christian. His movies, including It’s A Wonderful Life, reflect open-hearted idealism.

In the movie, small-town good guy Jefferson Smith, who leads a group of local boys, ends up in the U.S. Senate. There he finds himself among a group of much less innocent men. They reject his ideals, sure he will change or be distracted. He is advised to be pragmatic. When he won’t play along, forces try to stop him. In the end, it is the same group of boys who help good triumph.

What if Jesus visited Congress right now? Would Christian members believe him? Would they question whether he is the real Jesus? Would they argue that his interpretation of the Christian mission is wrong, even though it is his own words at issue?

Not for the first time, Jesus will still preach to these naysayers. Maybe he will filibuster, as Mr. Smith did until he collapsed in exhaustion. Jesus is no stranger to extreme public sacrifice in service of the greater good.

Will Mr. Jesus go to Washington? Many Republicans think he is already there. But is he really?

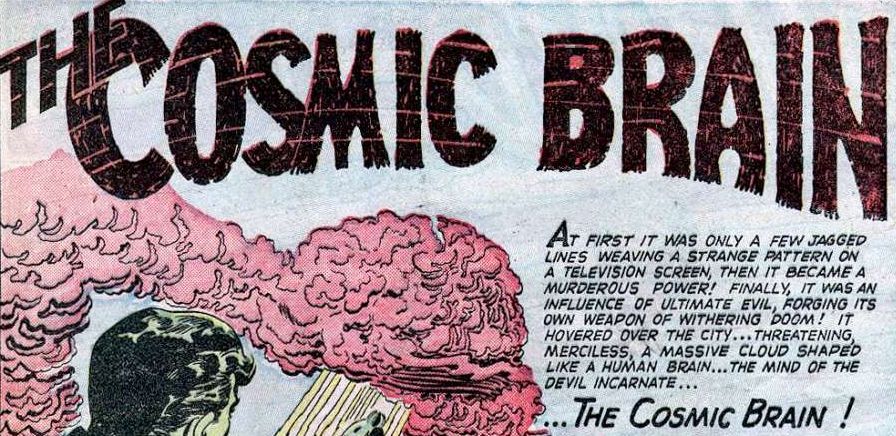

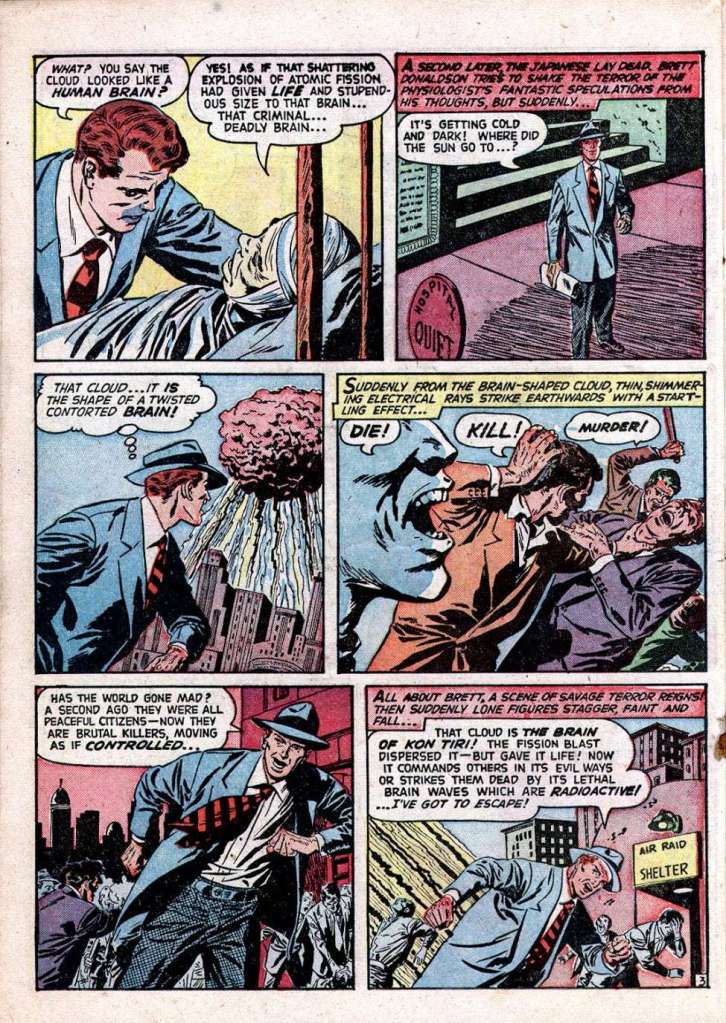

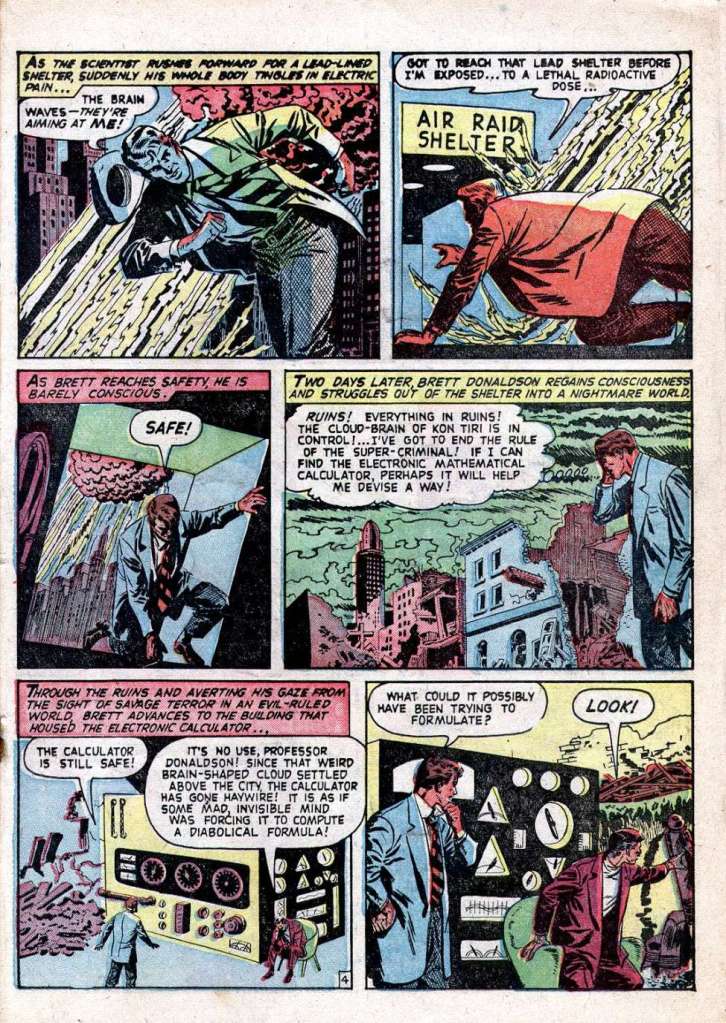

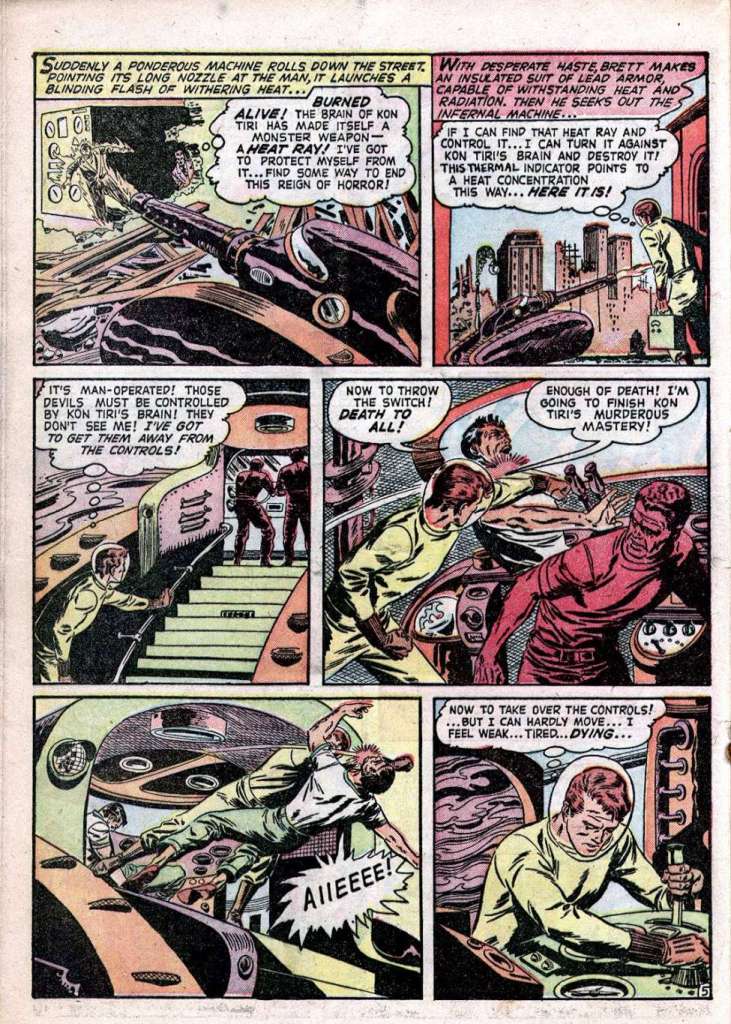

“At first it was only a few jagged lines weaving a strange pattern on a television screen. Then it became a murderous power! Finally, it was an influence of ultimate evil, forging its own weapon of withering doom…The mind of the devil incarnate…The Cosmic Brain.”

Amazing Adventures, May 1951

If you wonder how The Cosmic Brain was defeated, see the final page below.

There is a notable lack of compassion in some of the public initiatives in America and in other nations. These are nations that officially or unofficially identify as Judaeo-Christian.

For some time I’ve focused on that lack of compassion and considered how it might be improved.

But here I move to a predicate question. Why do those traditions or society value and promote compassion at all?

The question particularly arises for students of Buddhism. It may be an overbroad characterization, but it is not imprecise to say that compassion is at the center of Buddhism.

Which leads to the question of whether and how much compassion is at the center of other traditions.

So why compassion at all?

Here a few of the possible answers.

It is the right thing to do.

God wants it and expects it.

The Golden Rule advises it, because we will be treated as we treat others.

It will get us into heaven or keep us out of hell.

It makes us feel good.

Unlike those and other explanations, Buddhism reaches compassion not as an assigned transactional value but as an unavoidable conclusion. To simplify in my own substandard understanding, if there is absolute equality among us, there can be nothing but compassion. If we don’t recognize that absolute equality—and we so often don’t, instead putting ourselves in an unequal position—how can we be genuinely compassionate?

With that, back to the events of the day, and the open question of how, once we have advanced our own compassion, we can find ways to advance it in our traditions and in our nations.

The danger of a lie is directly proportional to the power of the liar.

For example: If someone stands in front of you pointing a gun and says, “The gun isn’t loaded” or “I won’t shoot you”, these might both be lies. A loaded gun is powerful. If those assertions are lies, it is possible you will in fact be shot, injured or killed.

If someone is a chronic or pathological liar and is in a powerful position, it would be prudent not to believe anything he says. Not just skeptical, but believing nothing. Some of those lies may be less consequential, but many of those lies are dangerous.

As for those who choose to believe the lies, sometimes all the lies, history is filled with that. And filled with the dangers that ensued.

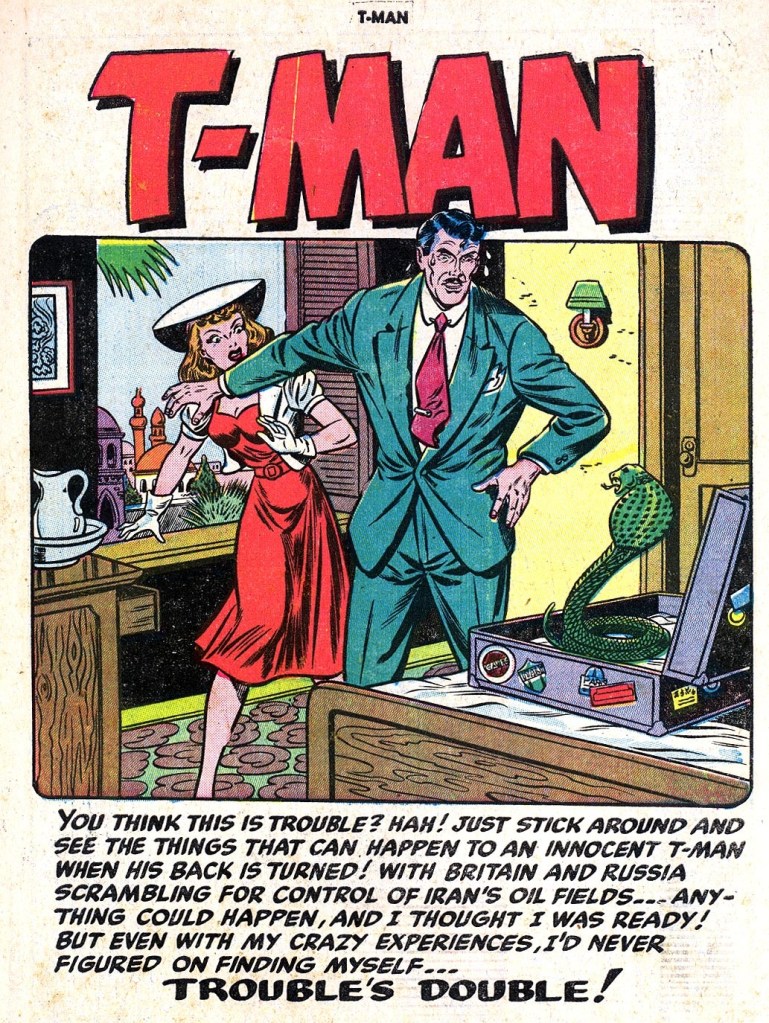

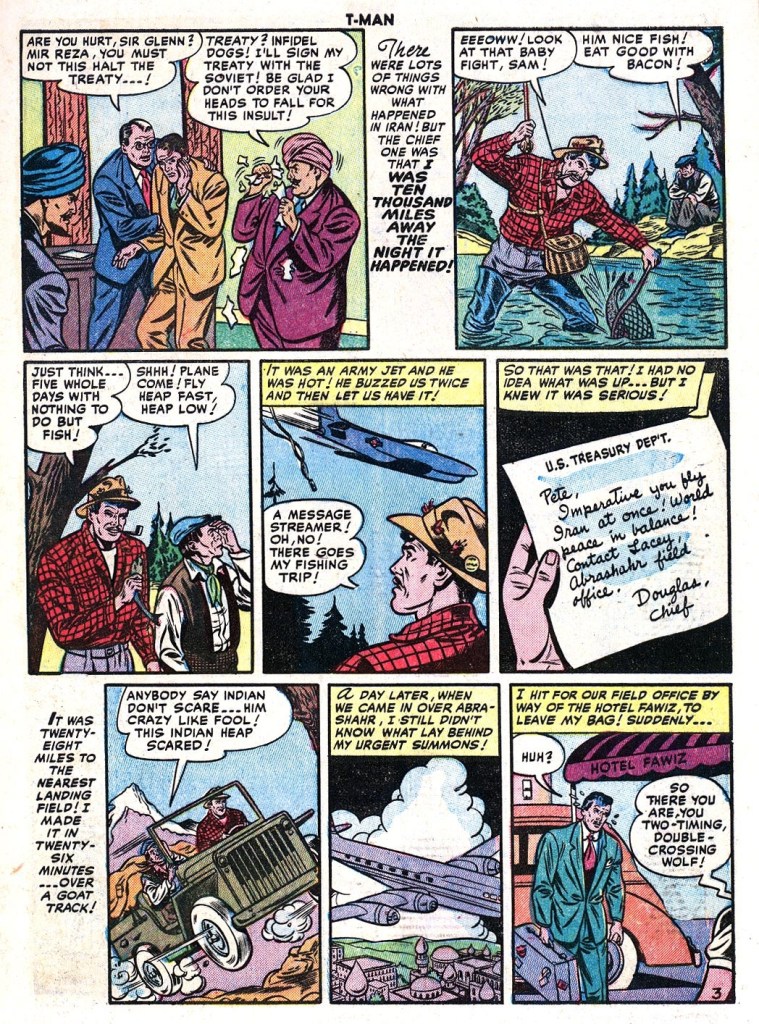

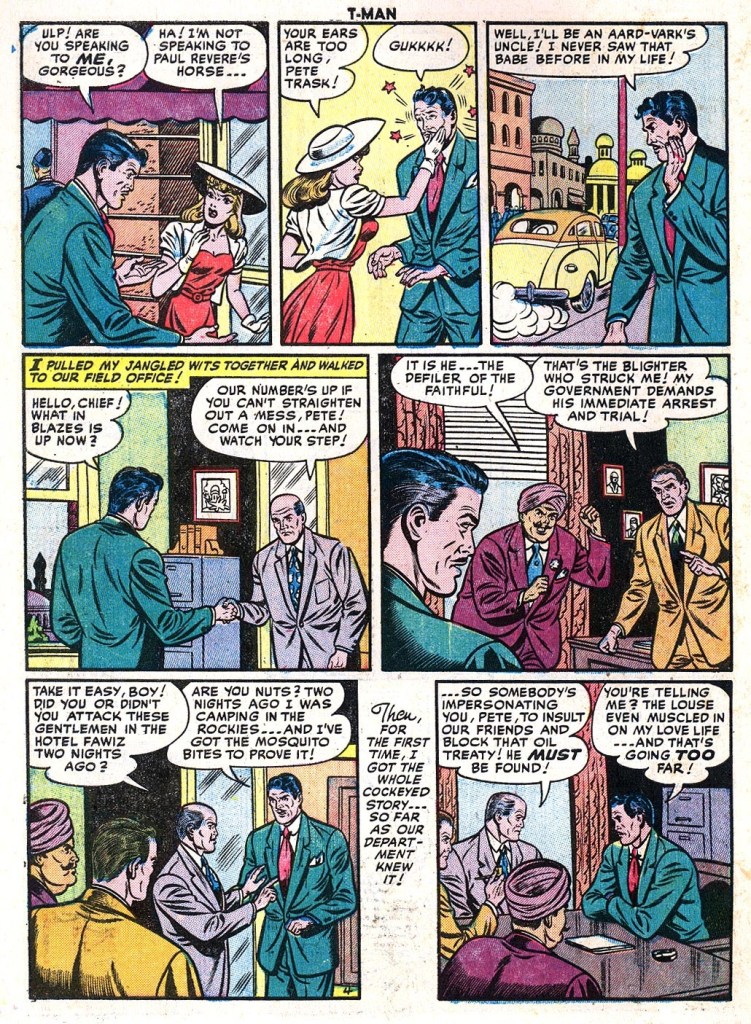

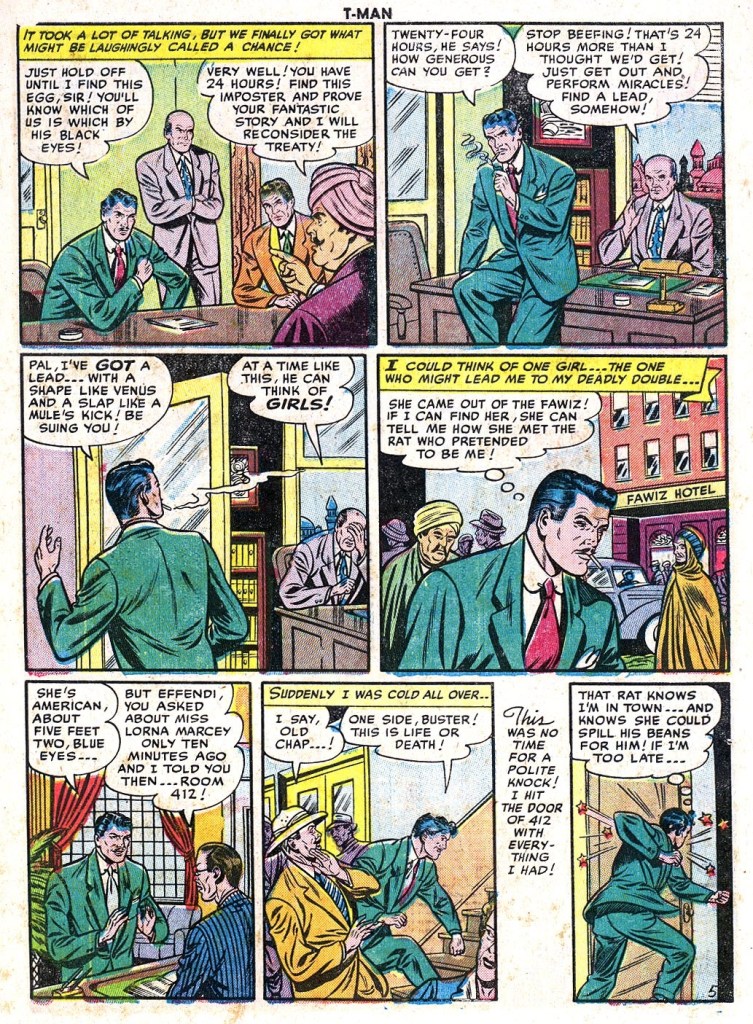

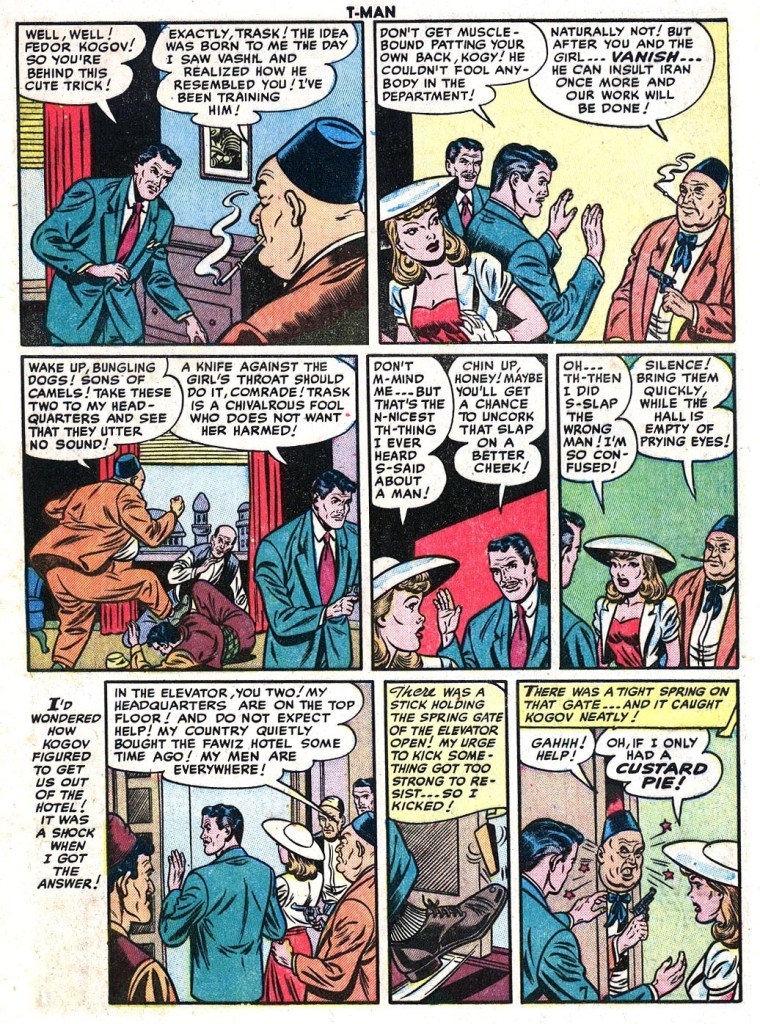

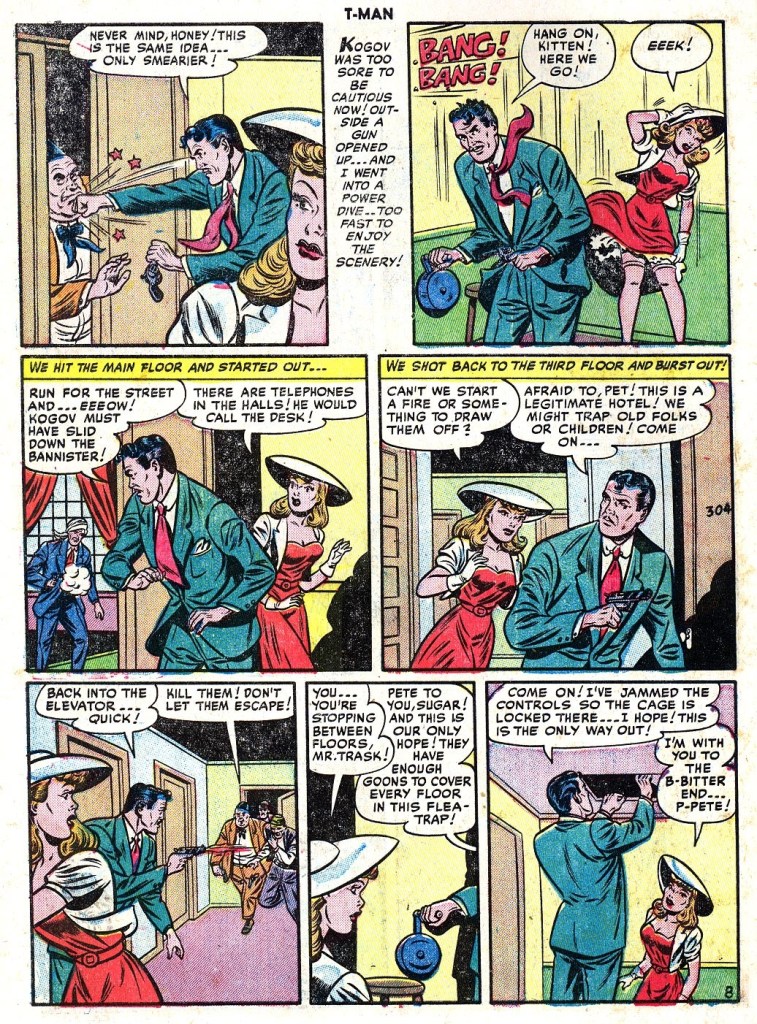

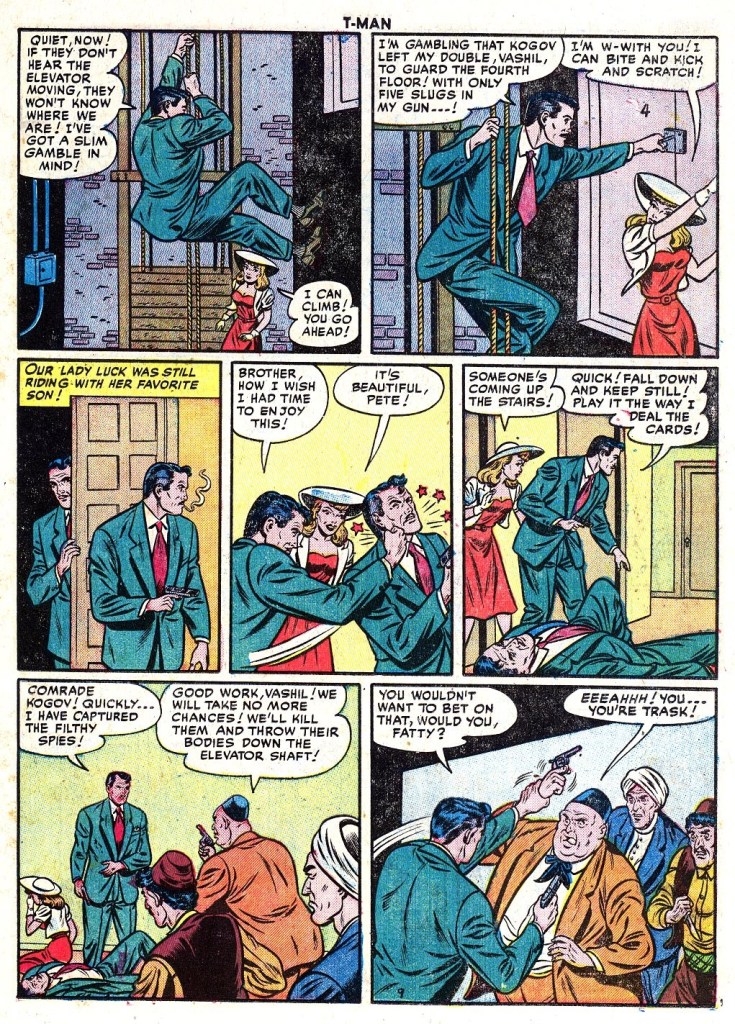

T-Man (Treasury agent) Pete Trask traveled the world to fight bad guys (anti-Americans and Communists) from 1951 to 1956. The comic books chronicle “authentic cases based on the files of the U.S. Treasury Department”.

Below are the pages of an exciting story, Death Trap in Iran, from the January1952 issue of T-Man. T-Man is in Iran to protect the oil fields from Iranian bad guys:

“With Britain and Russia scrambling for control of Iran’s oil fields…anything could happen, and I thought I was ready! But even with my crazy experiences, I’d never figured on finding myself…Trouble’s Double!”

This is part of my ongoing mission to understand and explain world events in terms of comic books from the 1930s to the 1960s.

Sending the garden

The garden is awake

Growing colorful in the rising sun

What good is it for me?

I send it to those who need it most

That their suffering will soften with joy

“Since I affirm nothing, no one can refute my point of view.”

This saying, valuable for individuals and the world, is from Nagarjuna (1st-2nd century CE), arguably the most influential Indian Buddhist thinker after Gautama Buddha.

The Middle Way does not suggest that we hold no views. Buddhism, along with every religious tradition, distinguishes between right views and wrong views. So do philosophical, political, social and cultural traditions of all kinds. We can’t and won’t stop holding views.

The Middle Way does say that such views, as essential as they seem, are also empty and nonexistent, mere creations of our minds. That they guide our actions in our lives and the world is undeniable. But to the extent we embrace them tightly, it is the source of trouble in our lives and the world.

Nagarjuna is correct, not just as a matter of logic but as a matter of living with ourselves and others. Views, what we learn and discern as right views, can guide us. When we also see those views as empty, not to be attached to, it is less likely those views will drive us to unnecessary confrontation. There is no refutation when there is no affirmation.

I went to the crossroad, fell down on my knees

The best case for the electric guitar (pun accidental, I think) is those who have mastered it.

I was going to begin with a partial list of favorite players and giants (bigger than great). But artistic lists are pointless—though admittedly fun—so they are unhelpful. Anyway, that list would be really long.

Instead, when I listened this morning to Wheels of Fire (1968) by Cream, I was impressed by the guitarist, a then-young guy named Eric Clapton. I’m sure Clapton’s playing has gotten “better” over the decades, but his playing here is __ (fill in the superlative).

So here is Cream live, performing an electric version of the classic Robert Johnson song Cross Road Blues. Setting aside the meme at the time that “Clapton is God”, he is pretty good. Makes the case for electric guitars.

Also, as lover of Mississippi, blues, and rock and roll, I’ve included a recording of the original Robert Johnson version. They’ve added a fun video of the life and legend of Robert Johnson—he reputedly sold his soul to play so otherworldly great.

As you read this message from Chogyam Trungpa, from his book Training the Mind and Cultivating Loving-Kindness, you will find his unique way of talking about practice and wisdom in relatable conversational ways.

This is about a concept that is hard for even the best teachers to put in a short and easy form. Hard because, on top of its complexity, it refers to an aspirational experience and not just a concept. So this very brief excerpt can’t possibly do it justice.

But his description of how we think about our thoughts is worth passing on, even if the antidote is treated by Trungpa and others at greater length and with more clarity. I recognize myself and maybe you will too.

Seeing confusion as the four kayas

Is unsurpassable shunyata protection.

As you continue to practice mindfulness and awareness, the seeming confusion and chaos in your mind begin to seem absurd. You begin to realize that your thoughts have no real birthplace, no origin, they just pop up as dharmakaya*. They are unborn. And your thoughts don’t go anywhere, they are unceasing. Therefore, your mind is seen as sambhogakaya. And furthermore, no activities are really happening in your mind, so the notion that your mind can dwell on anything also begins to seem absurd, because there is nothing to dwell on. Therefore, your mind is seen as nirmanakaya. Putting the whole thing together, there is no birth, no cessation, and no acting or dwelling at all—therefore, your mind is seen as svabhavikakaya. The point is not to make your mind a blank. It is just that as a result of supermindfulness and superawareness, you begin to see that nothing is actually happening—although at the same time you think that lots of things are happening.

Realizing that the confusion and the chaos in your mind have no origin, no cessation, and nowhere to dwell is the best protection. Shunyata** is the best protection because it cuts the solidity of your beliefs. “I have my solid thought” or “This is my grand thought” or “My thought is so cute” or “In my thoughts I visualize a grand whatever” or “The star men came down and talked to me” or “Genghis Khan is present in my mind” or “Jesus Christ himself manifested in my mind” or “I have thought of a tremendous scheme a for how to build a city, or how to write a tremendous musical comedy, or how to conquer the world”—it could be anything, from that level down to: “How am I going to earn my living after this?” or “What is the best way for me to sharpen my personality so that I will be visible in the world?” or “How I hate my problems!” All of those schemes and thoughts and ideas are empty! If you look behind their backs, it is like looking at a mask. If you look behind a mask, you see that it is hollow. There may be a few holes for the nostrils and the mouth—but if you look behind it, it doesn’t look like a face anymore, it is just junk with holes in it. Realizing that is your best protection. You realize that you are no longer the greatest artist at all, that you are not any of your big ideas. You realize that you are just authoring absurd, nonexistent things. That is the best protection for cutting confusion.

Chogyam Trungpa

*kaya: Literally, “body.” The four kayas refer in this text to four aspects of perception. Dharmakaya is the sense of openness; nirmanakaya is clarity; sambhogakaya is the link or relationship between those two; and svabhavikakaya is the total experience of the whole thing.

**shunyata: “Emptiness,” “openness.” A completely open and unbounded clarity of mind.