Government of the Absurd

by Bob Schwartz

“Nothing happens, nobody comes, nobody goes, it’s awful!”

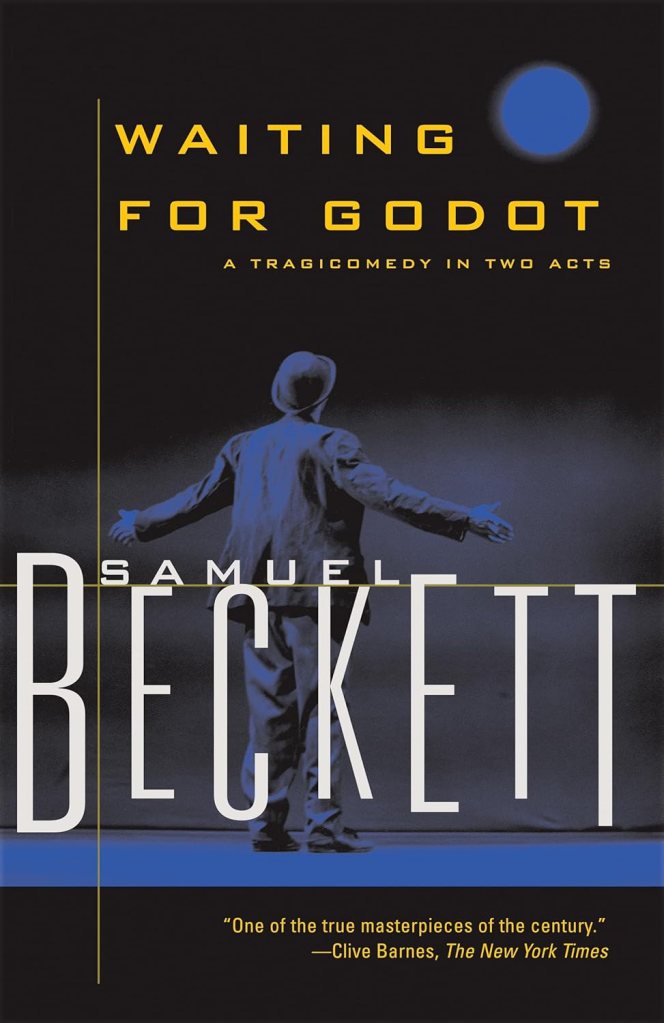

Estragon in Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett

Theater of the absurd is a term coined by Martin Esslin in his 1961 book by that name. It describes a dramatic movement that started in Europe after World War II and moved across the theater world in the1950s and 1960s.

Playwrights associated with the movement include Samuel Beckett, Eugene Ionesco, Jean Genet, and Harold Pinter. They wrote plays that looked very little like the three-act dramas audiences were accustomed to. The dialogue might not make sense, filled with non-sequiturs. The action might not follow a sensible pattern, if there was action at all.

In a word, absurd. Which might describe the world that hatched these plays, a world that followed a second world war following a first world war that was “the war to end all wars” but didn’t, a second world war that gave us human horror and a weapon that could be described as “the weapon to end all wars and everything else”. And in all spheres of politics, economics, technology, society and culture, things were changing at a pace unseen and unknown. Making sense of it seemed nearly impossible, so why bother trying? If all of it didn’t make sense, why should our plays, or our books, or our art? Or our government?

The most famous of these plays is Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. Two tramps engage in dialogues about nothing in particular, as they wait for the arrival of the mysterious Godot—who never arrives. In the end, the two of them stay exactly where they began on stage. One of them, Estragon, describes their situation perfectly: “Nothing happens, nobody comes, nobody goes, it’s awful!”

American governments have been many things, as have governments around the world throughout history. Smart and stupid, honest and corrupt, benign and evil, successful and failed. Sometimes things in government might seem silly or nonsensical, but a closer look reveals an understandable motive.

What makes this moment in American government different, even if we attribute much of it to some master plan or to one man’s disorderly psyche, is that things simply don’t entirely make much sense. If you wrote a play that included the more outrageous monologues of the American president, you could easily categorize them as theater of the absurd. Or government of the absurd.