When the going gets weird, the weird turn pro.

Hunter S. Thompson

About a week ago, President Obama said that if Syria’s Bashar Assad was not stopped from using chemical weapons, we might find those same weapons used against America. When asked about this days later, a presidential spokesman ignored the question. This weekend Secretary of State John Kerry said that the decision to stop Assad’s use of the weapons was a “Munich moment.” Meaning: Just as the Munich Agreement of 1938 condoned Hitler’s occupation of Czech territory, emboldening and enabling his vision of global conquest, so would our failure to respond to Assad’s use of chemical weapons further his insidious master plan.

Experts who have bothered to talk about the prospect of these chemical weapons being used against America have dismissed it out of hand. As for the “Munich moment,” that requires a bit more nuance. Nobody claims, at least not yet, that Assad has any extra-territorial plans or delusions of regional grandeur. His plan seems to be simply to punish any Syrians who stand in the way of him and his family fiercely holding on to power. Garden variety despotry; Assad is no Hitler. If “Munich” means appeasing his inhumanity, that is also silly. The bulk of Assad’s inhumanity is also garden variety: guns, bombs, etc. Nothing that Obama has proposed is intended to take care of that.

The region really did have a Munich moment in 1990. Saddam Hussein invaded and annexed Kuwait. A thirty-four nation coalition, led by the U.S., pushed him back to his own borders. Both the history of the Gulf War and its aftermath—including the decision by Bush 1 to go no further and the decision by Bush 2 to finish the job—are beyond the scope of this note. This is just to say that if you want to know what a Munich moment looks like, that was it.

The authenticity and civility of our political life are always in question. We ask whether politicians and their supporters are speaking truth, saying what they mean, meaning what they say, and saying it all in a way that is reasonably respectful and polite. That’s a lot to ask of them, and our expectations are right now pretty low. It’s also a lot to ask of political pundits and commentators. Unconstrained by the limitations of office or election, some of them, left to right, go wherever their opinions take them. Fish gotta swim, birds gotta fly.

Then there are political journalists. This is where things get tricky. Calling a political statement a lie or stupid, or calling a politician a liar or stupid, is supposed to fail the professional standard on a few scores. It supposedly puts a journalist’s objectivity in question; that sort of discourse is best left to political minions and commentators. And if not carefully couched or softened, it can come off as inappropriately impolite and uncivil, another professional faux pas.

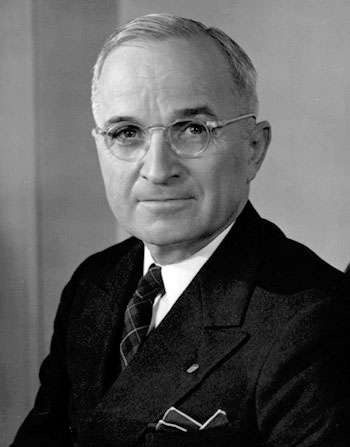

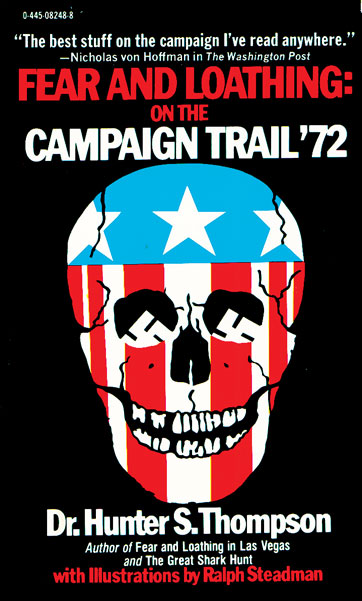

We should all miss Hunter S. Thompson right about now. His suicide in 2005 left a gap in political journalism that hasn’t been filled and probably never will be. He didn’t begin as a political reporter. He came up as a writer during the time of the so-called “new journalism” in the 1960s (Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, et al), when the lines between the factual, the personal and the expressive broke down. By his own admission, Thompson was crazy, formally or informally; he was also a stunningly talented observer and writer. When he hit the political beat, it was right place, right time, right writer. If politics was an exercise in duplicity, venality and near-insanity, it needed a professional journalist just as insane. The collection of his Rolling Stone coverage of the 1972 presidential election, Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail, is not just on another planet from the classic campaign coverage up to then; it is in another solar system.

Thompson had a special relationship with Richard Nixon. He ended up respecting and applauding Nixon’s brilliant mind as an expert football strategist, but otherwise Thompson despised him. He wrote a 1994 obituary of Nixon. In it he continues the case for that untempered loathing, but in this excerpt also explains why it is an appropriate attitude for a journalist:

Kissinger was only one of the many historians who suddenly came to see Nixon as more than the sum of his many squalid parts. He seemed to be saying that History will not have to absolve Nixon, because he has already done it himself in a massive act of will and crazed arrogance that already ranks him supreme, along with other Nietzschean supermen like Hitler, Jesus, Bismarck and the Emperor Hirohito. These revisionists have catapulted Nixon to the status of an American Caesar, claiming that when the definitive history of the 20th century is written, no other president will come close to Nixon in stature. “He will dwarf FDR and Truman,” according to one scholar from Duke University.

It was all gibberish, of course. Nixon was no more a Saint than he was a Great President. He was more like Sammy Glick than Winston Churchill. He was a cheap crook and a merciless war criminal who bombed more people to death in Laos and Cambodia than the U.S. Army lost in all of World War II, and he denied it to the day of his death. When students at Kent State University, in Ohio, protested the bombing, he connived to have them attacked and slain by troops from the National Guard.

Some people will say that words like scum and rotten are wrong for Objective Journalism — which is true, but they miss the point. It was the built-in blind spots of the Objective rules and dogma that allowed Nixon to slither into the White House in the first place. He looked so good on paper that you could almost vote for him sight unseen. He seemed so all-American, so much like Horatio Alger, that he was able to slip through the cracks of Objective Journalism. You had to get Subjective to see Nixon clearly, and the shock of recognition was often painful.

It’s not that we don’t have good and great political journalists working today; we may have more than ever. And it’s not that there aren’t plenty of partisans pointing out gaps in someone else’s facts and reasoning.

It’s just that an amazing amount of stuff gets said and seems to get by far too unchallenged or challenged too narrowly or politely. It wasn’t so long ago that the Republican party produced a nominating spectacle that is widely characterized as a circus or a clown car. But at the time, journalists were unwilling to even hint at how ridiculous some of it was, as the party of Lincoln earnestly considered nominating Herman Cain or Donald Trump as their standard bearer.

Sure we need objectivity, maybe now more than ever in a social media enriched/poisoned environment. What we shouldn’t do is confuse objectivity with comity and politeness. If Hunter Thompson was shockingly blunt—and so much fun to read—it was to wake people up from the soporific effect of treating truth and lies, intelligence and stupidity, as rhetorical equivalents, in the name of objectivity, politeness and respect. In the name of keeping the peace. That would be the media Munich moment.

Update: Rereading this post, I have to add that the closest we come to Hunter S. Thompson’s “gonzo” political journalism is The Daily Show on Comedy Central. This revelation came watching the first few days of Jon Stewart’s return after his summer away, coming back to a grim and arguably ridiculous political crisis. The Daily Show’s trick is to protest (too much) that it is a “fake” news show, which gives it total license to completely get its facts straight while speaking truth to absurdity. And when, as this week, vicious jokes aren’t quite enough, Stewart vents his frustration directly and straight, no humor. Oh, to see what The Daily Show would have made of the Nixon Years.